Posts

Posts Likes Received

Likes ReceivedIs cross-border e-commerce a "land of hope" or a "mediocre endeavor"?

In our previous overview of the general e-commerce industry, "Roaring Against the Wind," it can be seen that the domestic e-commerce business is basically in a stagnant state under the dual pressure of consumer headwinds and fierce competition. Unless there is a rebound in the subsequent "Double Eleven" promotion and 4Q data, it is difficult to find trend-based investment opportunities in the domestic e-commerce business alone.

However, if we change our perspective, the overseas business of domestic e-commerce platforms can be considered as "rising tides." Regardless of the fact that Shein and Shopee were once valued at billions of dollars during the peak of prosperity, even in the current downturn in the overseas e-commerce industry, "domestic" cross-border e-commerce platforms such as Temu and TikTok Shop have still achieved explosive growth against the trend, attracting considerable attention in both domestic and international capital markets.

Therefore, this article focuses on cross-border e-commerce, starting with an industry-level discussion and analysis of whether cross-border e-commerce can be considered a good business and what the differentiation and core competitiveness of this business model are. It also serves as the basis and framework for our subsequent in-depth research on specific companies.

The following is the detailed content of the article:

I. What kind of industry is cross-border e-commerce?

1. The scale of cross-border e-commerce

Generally, when studying a new industry, the first question to understand/judge is the scale (ceiling) of this industry, and how much growth space and speed it has in the future.

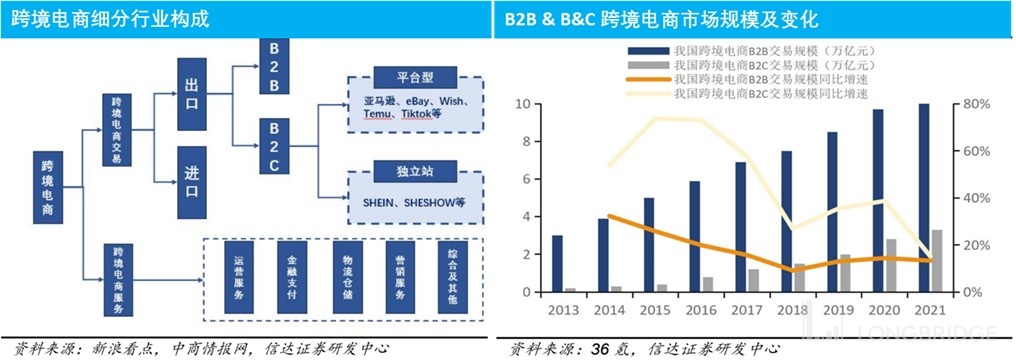

By definition, any online channel/tool that helps facilitate cross-border trade in goods falls within the scope of cross-border e-commerce and can be broadly divided into B2B and B2C models.

In the B2B model, most platforms only serve as a showcase for displaying and matching product information between sellers, and the subsequent transactions are mostly negotiated and completed by the buyer and seller themselves (possibly offline or outside the platform). Therefore, B2B platforms generally do not have a high value in the cross-border e-commerce transaction chain, and there are no companies of significant scale in this segment.

Similar to common domestic e-commerce platforms, B2C cross-border (export) e-commerce platforms (such as Amazon, Temu, AliExpress, etc.) play a dominant role in the entire transaction chain. However, unexpectedly, if we consider market size, it is the B2B model that dominates the cross-border e-commerce industry, with a scale of more than twice that of the B2C model. This actually reflects that traditional B2B channels are still mainstream in cross-border trade in goods.

In comparison, the B2C model has a lower share (penetration rate below 30%) in the entire cross-border e-commerce sector but is a "new channel" with faster growth. The scope of our discussion in the following sections mainly focuses on B2C cross-border e-commerce.

Looking at the B2C cross-border e-commerce market, the market size is approximately RMB 3-3.5 trillion (about USD 800-900 billion), which is equivalent to 1/4 to 1/3 of the scale of the domestic e-commerce market (12-13 trillion RMB). It can be seen that the current scale of cross-border e-commerce is already considerable, and considering the higher growth potential in the future, cross-border e-commerce is undoubtedly a market with significant incremental opportunities for domestic e-commerce platforms. 2. Who are the major players in cross-border e-commerce?

2. What are the major players in the market

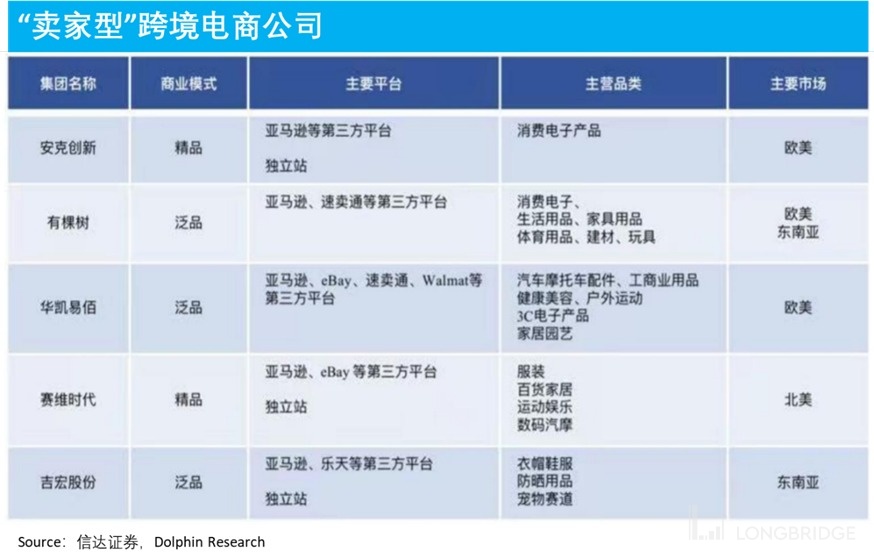

After answering the first question about the market size, the second question when researching a new industry is about the competitive landscape and the important "players" in the industry. In fact, since the development of domestic cross-border e-commerce around 2010, several companies have successfully gone public, and they can generally be divided into two categories: "seller-type" and "platform-type".

The "seller-type" players mainly rely on third-party e-commerce platforms, mainly Amazon, to sell cross-border goods and do not operate their own e-commerce platforms (or only have small independent sites). Among them, outstanding players such as Anker Innovations and Hisense Time have annual revenues reaching several billion RMB and valuations around several hundred billion RMB. However, "seller-type" players need to rely on other platforms and lack direct control over users and traffic. This "inherent flaw" determines that the scale limit and bargaining power of "seller-type" players are constrained by others, making it difficult for their valuations to exceed billions.

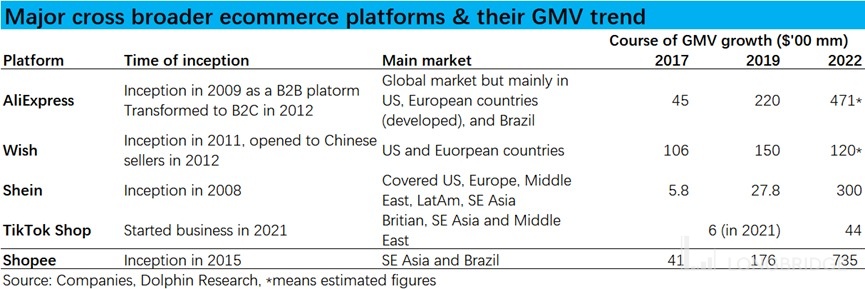

On the other hand, the "platform-type" players include: AliExpress, a global cross-border e-commerce platform under the Alibaba Group, which was established as early as 2009 and transformed into a B2C model in 2012; Shein, which was established in 2008 and has grown rapidly in recent years after transitioning to a "platform-type cross-border e-commerce"; Wish, founded by Americans but with a large number of sellers and products from China; TikTok Shop, the overseas version of Douyin's e-commerce, which started operating in early 2021 and is currently mainly developing in Southeast Asia and the Middle East; and Temu, under Pinduoduo, which is currently the most popular and rapidly growing platform.

In comparison, the top players among the "platform-type" players have achieved GMV and valuations in the hundreds of billions, with a significantly higher ceiling. Based on the brief development history of the top "platform-type" players listed in the table above, several rules can be preliminarily summarized: ① The target market of domestic cross-border e-commerce is generally focused on developed countries with high consumer purchasing power, such as Europe and the United States, as well as large-scale and fast-growing countries such as Southeast Asia, Brazil, and the Middle East. ② Most of the existing top platforms were established around 2010, but after more than a decade of development, their GMV scale is still between several tens of billions of dollars, and there has been no breakthrough to reach hundreds of billions, indicating that there is still a gap in scale compared to localized e-commerce with GMV in the trillions. This indicates that although cross-border e-commerce is a market with considerable potential, its ceiling is still much lower than that of localized e-commerce. Another case that can be used for verification is Shopee, the leading e-commerce platform in Southeast Asia, which was established in 2015. In its early days, Shopee mainly operated cross-border businesses from China to Southeast Asia, but later successfully transformed into a localized e-commerce platform. As a result, although Shopee has developed for 4-5 years less, its GMV (Gross Merchandise Volume) after localization is nearly 60% higher than that of Alibaba's largest cross-border e-commerce platform, AliExpress.

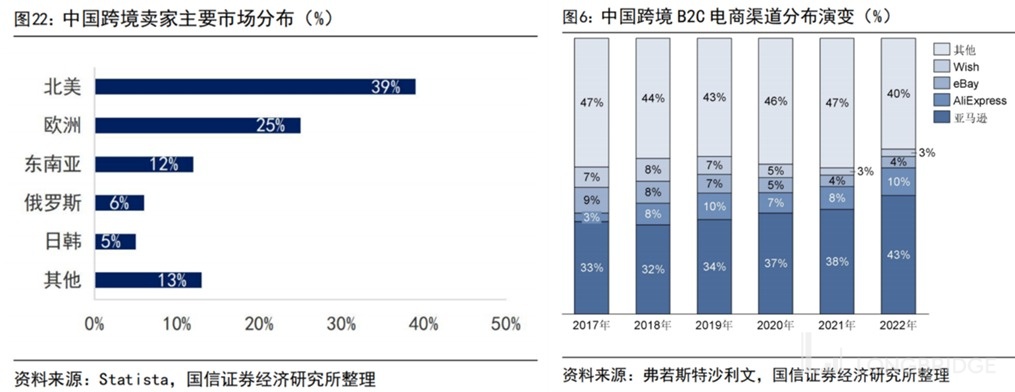

From the perspective of market competition, as shown in the graph, the market concentration of the domestic B2C cross-border e-commerce industry is not high. By 2022, the combined market share of the top four platforms is only 60%, and except for the largest player, the market share of the top 2 and below does not exceed 10%. Compared to the domestic leading e-commerce platforms that dominate almost all markets, the domestic cross-border e-commerce industry is still in a "multi-party melee" period, and the competition landscape has not yet solidified, nor has a true leader emerged.

Surprisingly but also logically, the largest cross-border e-commerce channel in China is not a platform originating from China, but Amazon, the largest e-commerce platform overseas, which accounts for about 40% of the market share in China's cross-border e-commerce. However, it is evident that Amazon belongs to the local e-commerce market in Europe and America, rather than being primarily engaged in cross-border e-commerce platforms for exporting Chinese goods. The reason why Amazon ranks first on the list is actually attributed to the numerous "seller-type" cross-border e-commerce players that rely on the Amazon platform.

The fact that Amazon, which should not have an advantage in the domestic supply chain of goods, is the largest "cross-border e-commerce platform" in China implies an important inference: even in the field of cross-border e-commerce, compared to having a large number of "affordable and high-quality" Chinese goods, having a large and high-quality overseas customer base is the key core competitiveness.

However, this is just a conjecture we deduced from the results. Whether this is true and how it can be explained in terms of business logic will be further explored in the future.

II. where is the core value/competitiveness of cross-border e-commerce?

From an industry perspective, B2C cross-border e-commerce has a considerable scale, a low penetration rate in the overall cross-border trade of goods, and the current market concentration is not high. In summary, it is a growth-oriented niche industry with many opportunities.

However, for cross-border e-commerce platforms to succeed in overseas markets, their main competitors are not only other cross-border e-commerce platforms, but also local e-commerce players and even local offline retail channels.

Therefore, the next question we need to discuss is: what are the core differences between cross-border e-commerce and local e-commerce and other channels? What is the core competitiveness of cross-border e-commerce?

Surface-level differentiation: low-priced goods in China & the fulfillment method of small parcel direct shipping. Based on common sense and intuition, the most obvious competitive advantage of cross-border e-commerce and overseas local retail channels (including online and offline) is the large number of "good quality and low price" goods from China. The key to the success of the cross-border e-commerce business model is to transport low-cost goods to consumer countries that are willing to pay relatively high prices, and profit from the price difference between the selling price and the cost.

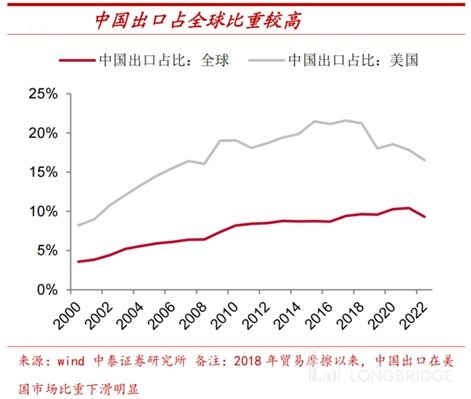

However, the problem is that cross-border e-commerce is not the only, and probably not the largest or best channel for overseas residents to purchase "good quality and low price" goods from China. In fact, in 2022, goods exported from China to the United States accounted for more than 15% of all imported goods in the United States (although it has declined significantly since the trade friction in 2018), making it one of the largest sources of imported goods in the United States. In other words, China's goods are not lacking in the traditional retail channels (online and offline) in the United States.

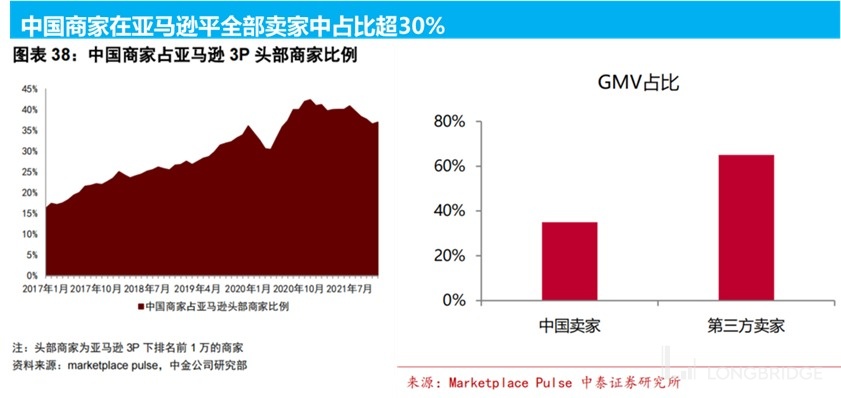

Even if we ignore the traditional channels for importing and exporting goods and only look at e-commerce channels, among all 3P sellers on the Amazon platform, the proportion of sellers from China exceeds 30% in terms of both quantity and GMV. Even without using domestic cross-border e-commerce platforms, Amazon users can still purchase a large number of goods produced in China.

Therefore, logically speaking, cross-border e-commerce platforms in China cannot provide significantly lower prices in the long term and maintain reasonable profits for goods that are also available through traditional channels or local e-commerce platforms in the United States.

Another obvious difference between cross-border e-commerce and traditional cross-border trade channels lies in the different fulfillment processes for different goods:

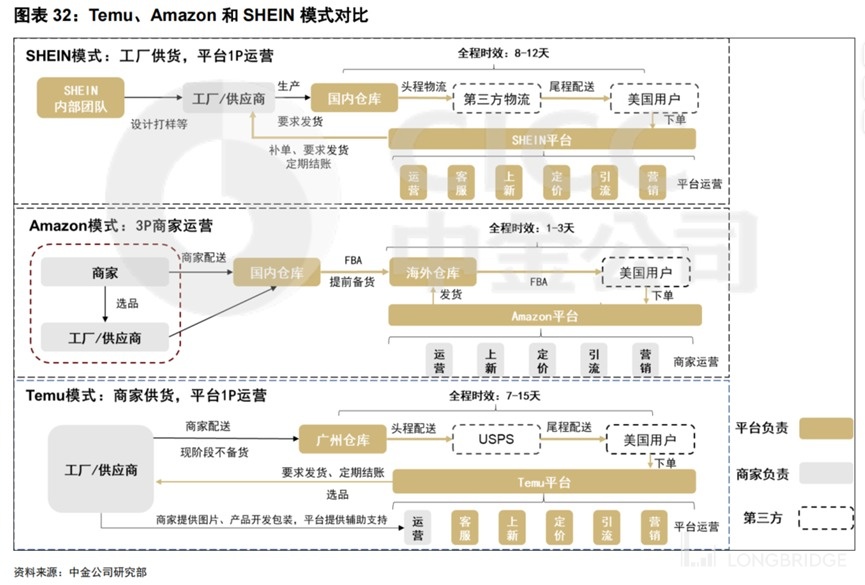

- Currently, most domestic cross-border e-commerce platforms adopt the fulfillment method of direct mail after the user places an order. The goods are transported through large-scale trunk transportation to the destination country, and then the final delivery is completed through local 3PL.

- In contrast, traditional sales channels or overseas e-commerce with local warehouse models mostly estimate the quantity in advance and transport them through trunk transportation to the destination country before the user places an order, and then sell them through local distribution channels or local e-commerce platforms.

Both of the above-mentioned channels actually adopt large-scale trunk transportation and use local logistics providers for final delivery after arriving in the destination country. Therefore, in terms of economies of scale and unit cost, there is no significant cost difference (possibly slightly higher) between the small package direct mail used by cross-border e-commerce and the process of traditional goods import and export.

The longer delivery time (around 10 days) under the small package direct mail model of cross-border e-commerce is not exchanged for lower delivery costs, but for lower inventory risks for platforms and merchants under the mode of customers placing orders before shipment. Therefore, merchants can accept lower profit margins. In summary, from the perspective of a healthy business model, domestic cross-border e-commerce platforms cannot maintain lower prices in the long term for a large number of Chinese goods that are already supplied overseas. The direct mail delivery model also does not have an advantage in terms of logistics costs, but it may help lower costs to a certain extent by reducing inventory risks and ultimately leading to lower prices.

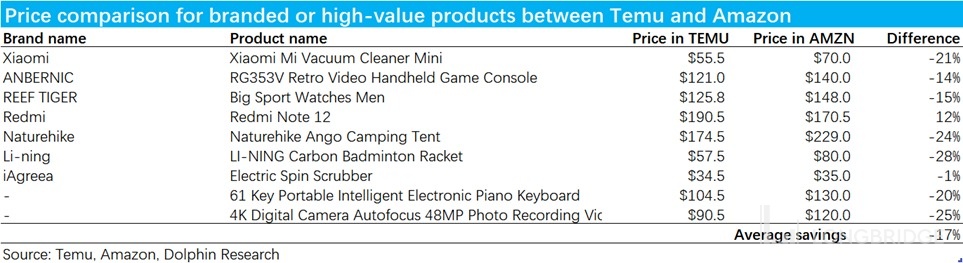

To verify the above judgment, Dolphin Research conducted a search on Temu for several branded or high-value goods (which are more likely to be sold in the United States). We found that Temu's prices for these types of goods have an average advantage of 17% compared to Amazon (although not significant).

In contrast, the prices of similar goods on Amazon that are only a few dollars on Temu are several times or even ten times higher.

Taking both into account, Temu's price advantage for goods mainly lies in the absolute low prices or non-branded goods, while for branded or specific model goods, Temu's price advantage is not that significant.

2. Long-tail goods are the core advantage and also the biggest constraint.

Based on all the previous analysis, we believe that the true core value of cross-border e-commerce lies in the long-tail goods that traditional import and export channels have not covered. These long-tail white-label goods are difficult (or not worth it) to predict their approximate sales volume and transport them across borders to target markets.

Domestic platforms such as Pinduoduo and Shein are more familiar with the supply chain of these long-tail goods, and the model of placing orders first and then delivering them avoids unpredictable inventory risks. Dolphin Research believes that this is the fundamental reason why domestic cross-border e-commerce platforms can still occupy a place in overseas countries where they are unfamiliar, have no user traffic, and lack awareness.

However, the biggest advantage is also the biggest constraint. The advantage categories of cross-border e-commerce are limited to low-priced goods such as white-label and long-tail products, while they have difficulty competing with domestic channels in high-value branded products. This clearly limits the variety of products that cross-border e-commerce can offer and the upper limit of the average order value.

From the perspective of user groups, in the absence of obvious price advantages, consumers are more inclined to familiar domestic channels rather than cross-border platforms with unclear origins. Similarly, the white-label products with relatively lower absolute prices are likely to attract a "stable user base" consisting of individuals with relatively lower incomes. As shown in the graph below, among Temu's user base, 55% of users have an annual income below $50,000, while only 14% have an income above $100,000.

The user base of cross-border e-commerce platforms is also likely to be mainly concentrated among individuals with lower incomes. And if they cannot have a broad and universal user base in overseas markets, it obviously limits the development potential of cross-border platforms.

Due to the aforementioned constraints, domestic cross-border platforms led by AliExpress have remained at a GMV volume of several hundred billion US dollars even after more than a decade of development. On the other hand, Amazon, as a local platform overseas, may not have advantages in terms of breadth and price compared to cross-border platforms originating from China, but with its stronger brand recognition among branded products and overseas users, it firmly occupies an absolute market share in the cross-border e-commerce business in China (40%+ vs. 10% for the second place).

3. Conclusion: As the most crucial conclusion of this analysis, Dolphin Research believes that if domestic cross-border export e-commerce platforms confine themselves to low-priced long-tail/white-label products and relatively low-income user groups, their upper limit is unlikely to exceed several hundred billion US dollars in GMV and similar valuation levels.

Only by transforming into localization, expanding products and users to all groups, and establishing a solid brand awareness among the majority of residents in the target market, can the vision of "creating another xx" be truly realized.

In this article, we have mainly discussed the cross-border e-commerce industry and the core differentiations and competitive advantages of this business model. In the future, we will have the opportunity to conduct more in-depth analysis on specific companies and explore how cross-border e-commerce can achieve localization and discover related investment opportunities.

<End>

Related research by Dolphin Research:

E-commerce Industry

October 10, 2023, "Against the Wind, Can Alibaba, JD.com, Meituan Make a Comeback?"

April 12, 2023, "Fierce Competition on Cost-effectiveness, When Will Alibaba, JD.com, Pinduoduo Stop Internal Competition?"

January 5, 2023, "The Offensive and Defensive Situation Reversed, Can Alibaba, Ctrip, Didi Launch a Counterattack?" On September 30, 2022, "[Pinduoduo vs Vipshop: Your 'poor days' are their 'good days'?" was published on Longbridge.

On September 22, 2022, "[Alibaba, Meituan, JD.com, Pinduoduo: Have they all resigned themselves? Still have to strive for 'great fortune'" was published on Longbridge.

On April 27, 2022, "[Alibaba vs Pinduoduo: After the bloodshed, only coexistence remains?" was published on Longbridge.

On April 22, 2022, "[Meituan, JD.com: Why are they performing well despite intense competition in the existing market?" was published on Longbridge.

On April 13, 2022, "[As the cycle declines, how much value is left for Alibaba and Tencent?" was published on Longbridge.

Risk disclosure and statement for this article: Dolphin Research disclaimer and general disclosure

The copyright of this article belongs to the original author/organization.

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not reflect the stance of the platform. The content is intended for investment reference purposes only and shall not be considered as investment advice. Please contact us if you have any questions or suggestions regarding the content services provided by the platform.