Has the US dollar peaked?

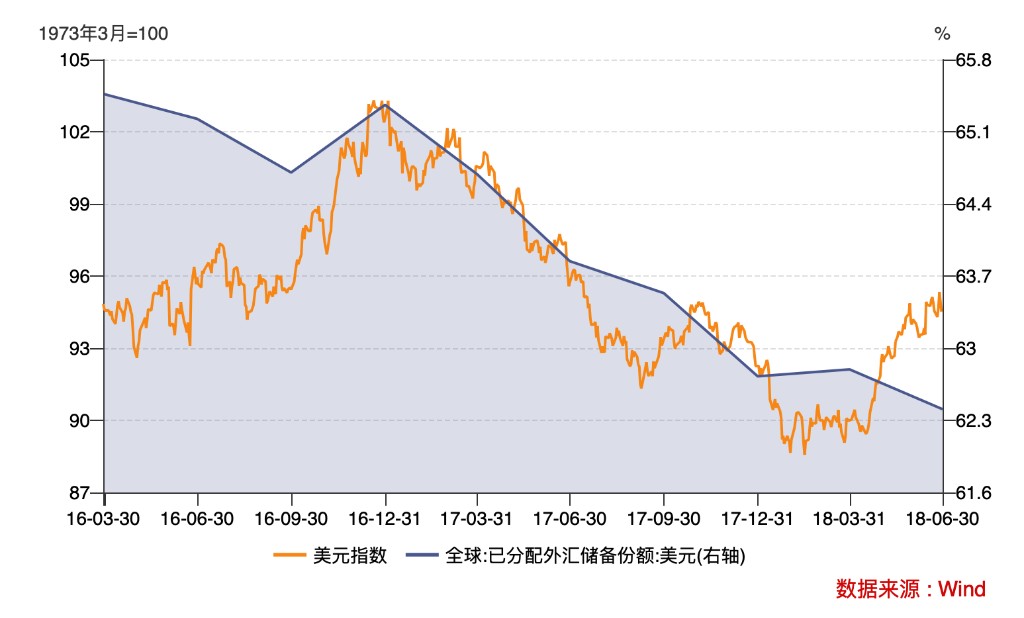

The US Dollar Index has risen nearly 9% since October, influenced by factors such as Trump Trade 2.0, a rebound in inflation, and a slowdown in the prospects of Federal Reserve interest rate cuts, reaching a high point not seen since the 2016 election. Historical data shows that the dollar fell continuously after peaking in 2017, mainly due to the Eurozone's economic recovery being stronger than that of the US and global central banks selling off dollar reserves. Currently, the market holds a cautious attitude towards the future trend of the dollar, which may face downward pressure

The US Dollar has "topped out"

Since October, the US dollar index has risen nearly 9%, driven by factors such as Trump Trade 2.0, inflation rebound, and a slowdown in the prospects of Federal Reserve interest rate cuts.

Compared to Trump Trade 1.0 after the 2016 election, the strengthening of the dollar since October has almost completely replicated that year and has already reached the "peak" at that time.

Does this mean the dollar should fall?

Why did the dollar plummet in 2017?

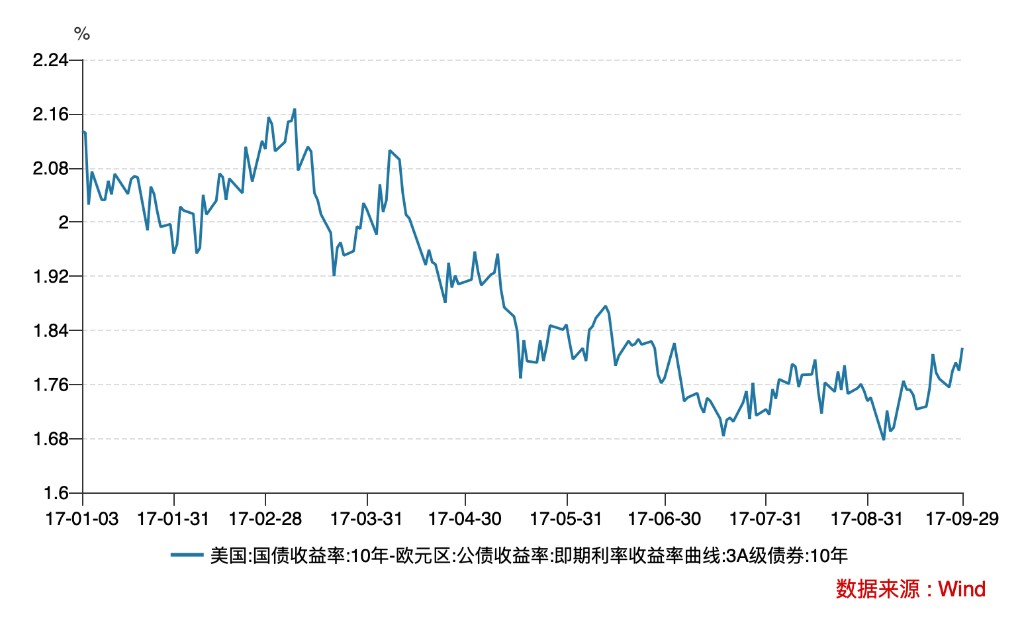

At the beginning of 2017, after reaching the peak of 102, the dollar index experienced three consecutive quarters of decline.

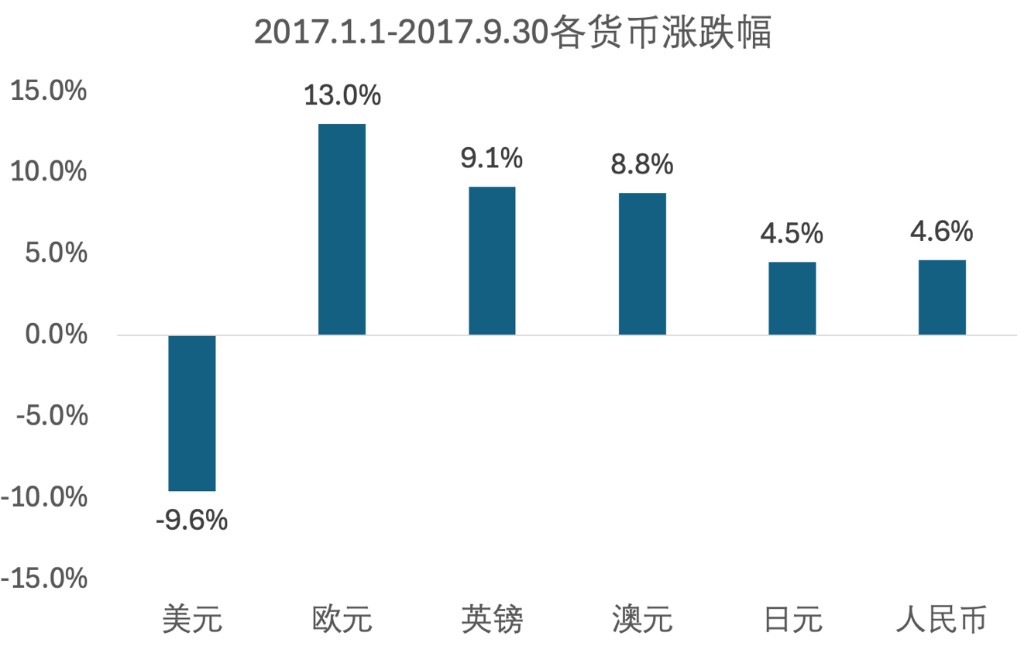

From January 1, 2017, to September 30, 2017, the dollar index fell by 9.6%, while during the same period, the dollar depreciated against the euro, pound, Australian dollar, yen, and renminbi by 13.0%, 9.1%, 8.8%, 4.5%, and 4.6%, respectively. It is evident that the strength of the euro was the main external driving force.

First, in terms of the economy, the recovery in the eurozone was even stronger than that of the United States.

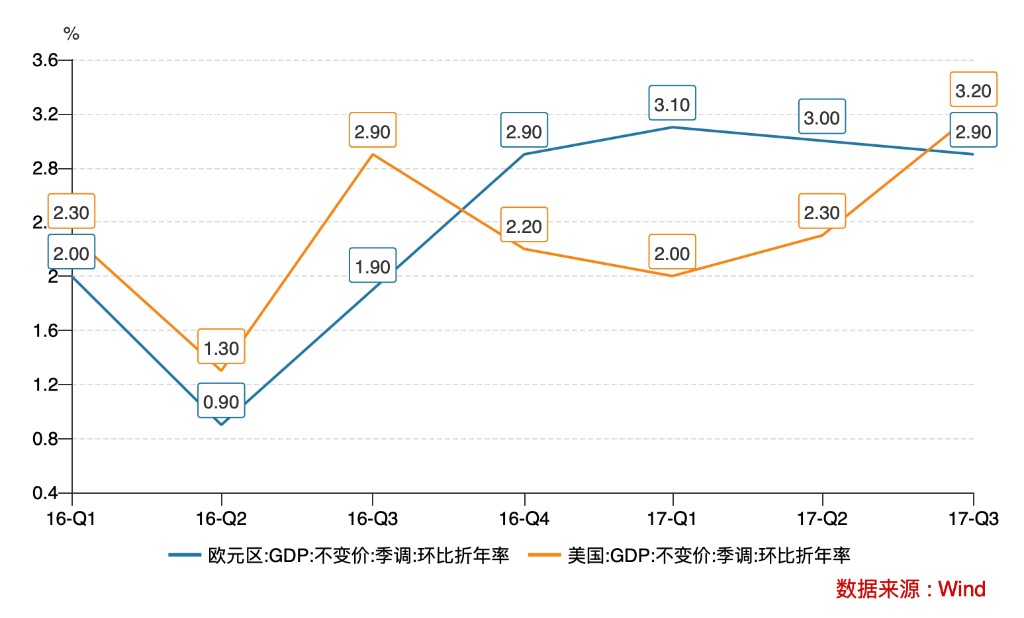

From Q4 2016 to Q3 2017, the eurozone's real GDP growth rates were 2.9%, 3.1%, 3.0%, and 2.9%, while the United States had rates of 2.2%, 2.0%, 2.3%, and 3.2%.

Since the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in 2011, the eurozone's economic growth has lagged behind that of the United States for many years. Therefore, even if the US economy was not weak in 2017, the accelerated recovery in Europe still pressured the dollar.

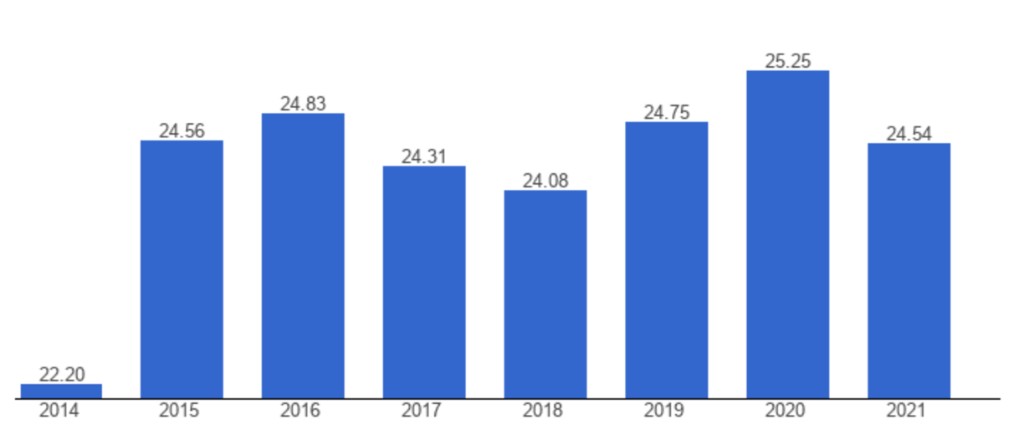

Another result of the relative changes in the US and European economies in 2017 was the decline in the US's share of the global economy.

Image: The percentage of the world's GDP accounted for by the United States (Source: World Bank)

As a result, central banks around the world significantly sold off their dollar reserves that year. The decrease in demand also constrained the performance of the dollar index.

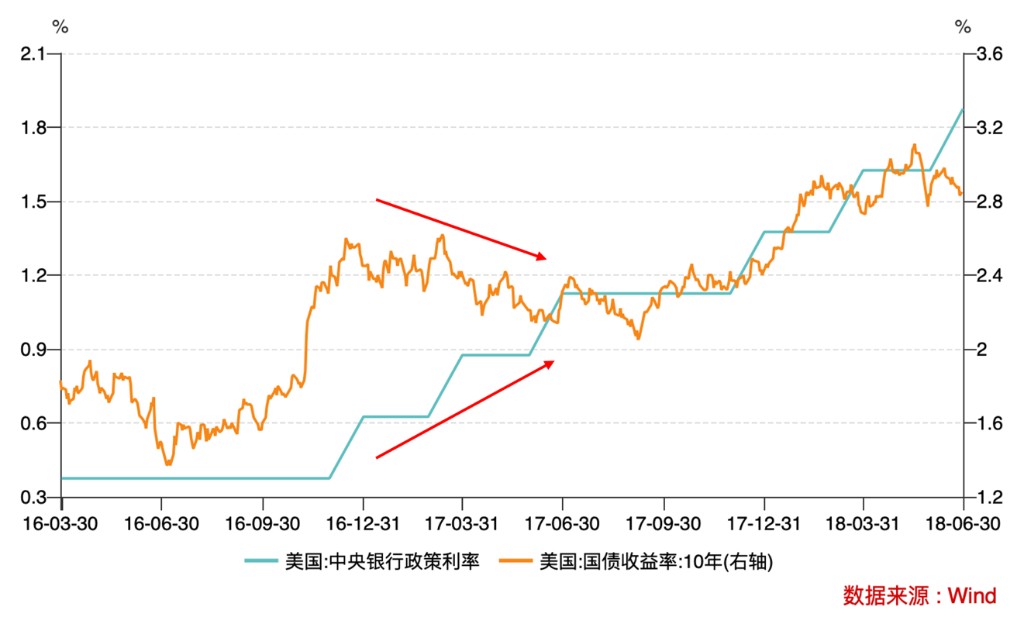

Secondly, in terms of monetary policy expectations, the eurozone was in the stage of preparing for interest rate hikes, while the United States was in the stage of implementing interest rate hikes. In fact, since the Federal Reserve indicated it would exit quantitative easing in 2013, only the Federal Reserve among the major global central banks has been committed to tightening monetary policy, which is the most important driver of the continuous rise of the US dollar from 2013 to 2016.

In 2017, the European Central Bank had not yet substantially reversed its low interest rate and quantitative easing policies, but it repeatedly signaled a tightening of monetary policy, leading the market to continuously "accumulate positions."

On the US side, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates three times in 2017, but the market had already prematurely digested the optimistic expectations for a strong dollar. When the Federal Reserve actually raised interest rates and Trump implemented tax reforms, the dollar was instead met with a release sell-off.

Furthermore, from the perspective of the political landscape at that time, the euro also exerted pressure on the dollar.

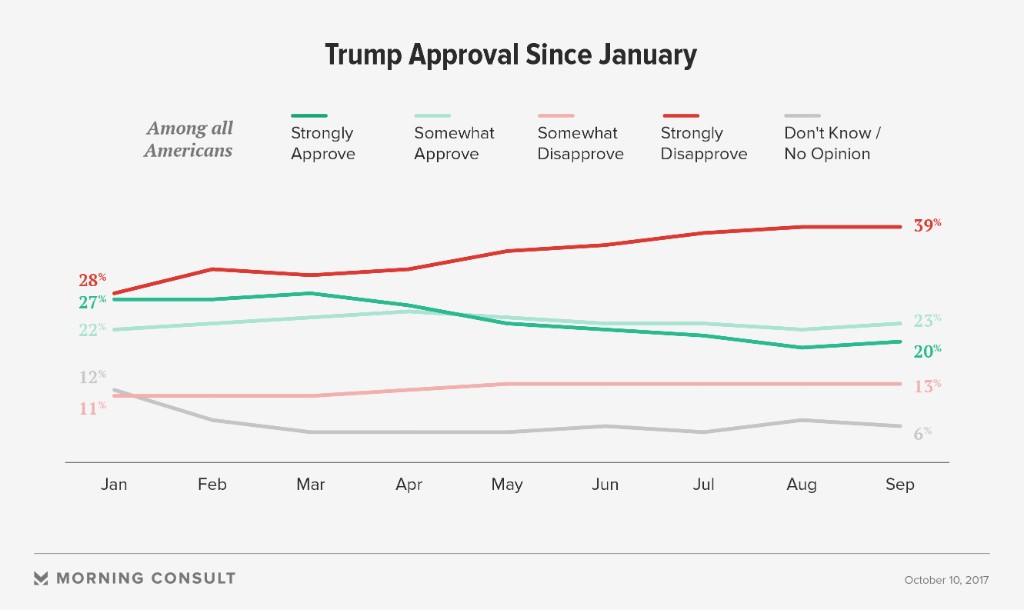

In the first half of 2017, the Trump administration faced varying degrees of difficulty in advancing healthcare reform, tax reform, infrastructure, immigration, and border wall policies, causing the market's initial optimism following Trump's election to turn pessimistic, even leading to the emergence of the "Trump disproof trade."

During the same period, important member countries of the Eurozone, such as the Netherlands, France, and Germany, successfully navigated domestic elections, with far-right parties losing, thus alleviating political tail risks. Especially after Macron was elected President of France, the market was very optimistic about his push for domestic structural reforms in France and further integration of the Eurozone.

US political expectations turned from hot to cold, while the EU's turned from cold to hot, further driving the euro's appreciation against the dollar.

So, does this round of a strong dollar face the aforementioned headwinds?