Streamlining: Lessons from Musk's Precedents

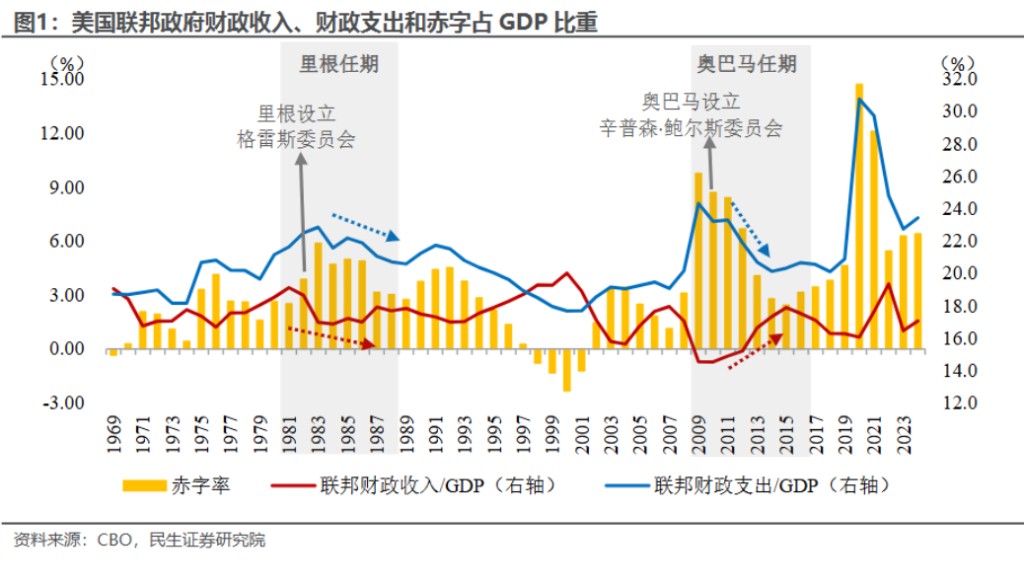

As Trump's inauguration approaches, the government efficiency department led by Musk is pushing for the streamlining of government agencies and personnel, resulting in the early resignation of several high-ranking officials. Agencies such as the Department of Education and the Environmental Protection Agency face the risk of cuts. Historically, both Reagan and Obama established committees to "trim the fat" from the government, but with limited results. The recommendations made by Reagan's Grace Commission saved a significant amount of money but did not meet expectations. Obama's Simpson-Bowles Commission also faced challenges. Whether the future "streamlining" will be successful remains to be seen

As Trump's inauguration approaches, the government efficiency department led by Musk seems to be "rubbing its hands": Not only has Musk himself "intervened" in the streamlined spending bill passed by Congress, but he has also sparked a wave of government agency and personnel closures and resignations (the Vice Chairman of the Fed, the FBI Director, and the SEC Chairman have announced their resignations in advance, and the State Department has announced the closure of its "Global Contact Center"). As a result, agencies such as the Department of Education, the Environmental Protection Agency, the IRS, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are also facing concerns about cuts.

After Trump's inauguration, how will the "government efficiency department" operate? Will the anticipated "streamlined government" be a "success" or a "flash in the pan"? Perhaps we can find relevant clues from history. Reagan and Obama also established temporary committees to formulate "downsizing" plans for the government: the Grace Commission and the Simpson-Bowles Commission; both provided detailed plans at the time, played a certain role in the short term, but did not achieve the expected results.

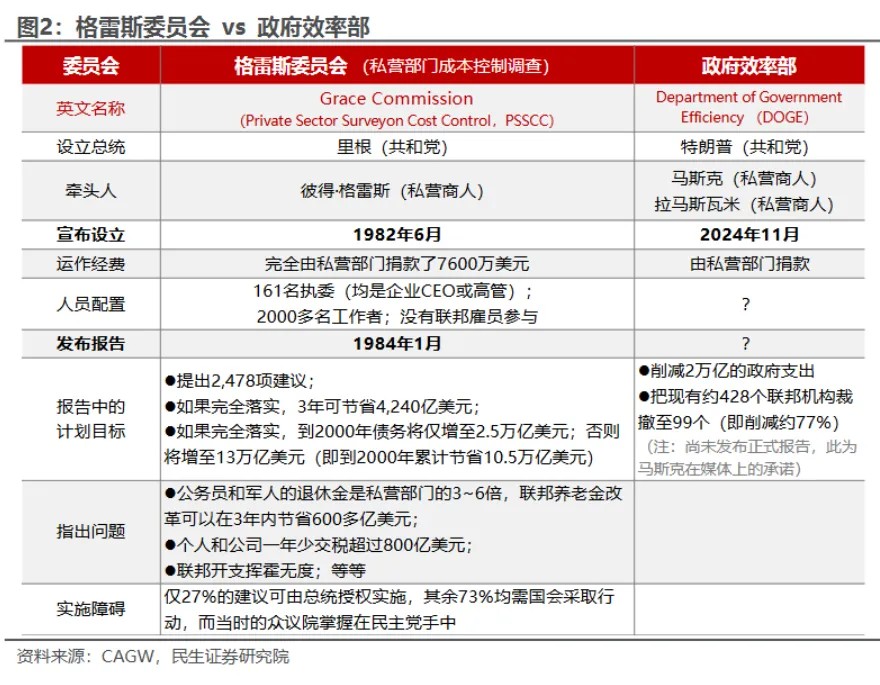

In June 1982, Reagan established the "Grace Commission" (Figure 2) to eliminate waste and inefficiency in the federal government. The commission was led by Grace and included 160 other executives from the industry. In January 1984, the commission released a report proposing 2,478 recommendations, aiming to save $424 billion within three years, and by 2000, it had cumulatively saved $10.5 trillion.

This report faced considerable skepticism, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Government Accountability Office reviewed about 400 of the recommendations (accounting for 90% of the total savings amount) and pointed out that the funds that could be saved were only one-third of the Grace Commission's estimated value. Whether private sector management experience can be applied to the public sector has also been a topic of controversy.

Some of the recommendations in the report were adopted, but the implementation of those requiring congressional review was limited. Overall, Reagan did achieve a "smaller government," reducing the size of the federal government by 5%. During his term, he promoted tax cuts and spending reductions, leading to a decline in both the ratio of fiscal revenue and expenditure to GDP.

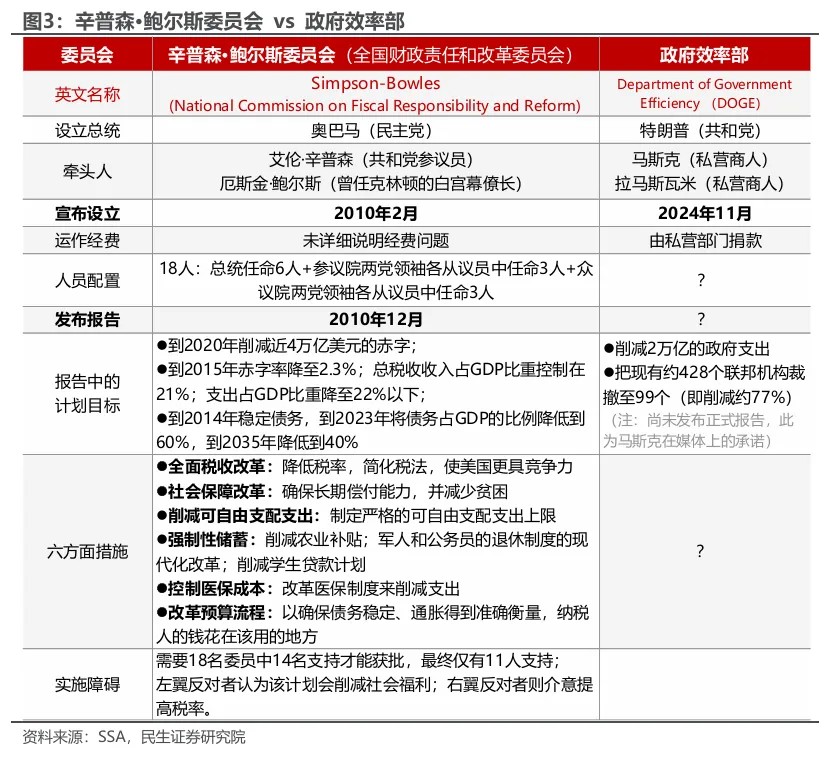

In January 2010, Obama established the "Simpson-Bowles Commission" (Figure 3) as a bipartisan government organization to study methods for reducing the deficit. The commission consisted of 18 members, led by Simpson and Bowles.

In December 2010, the commission released a report, aiming to reduce the deficit by $4 trillion by 2020; to bring the deficit rate down to 2.3% by 2015; to stabilize the debt by 2014; to reduce the federal debt to 60% of GDP by 2023; and to reduce it to 40% by 2035 The report needs the support of 14 out of 18 committee members to be approved, but ultimately only received 11 votes in favor. Although the report was not adopted, it left important guiding experiences for deficit reduction, and some recommendations were reflected in subsequent government policies.

Historically, what expenditure items might the "Department of Government Efficiency" cut?

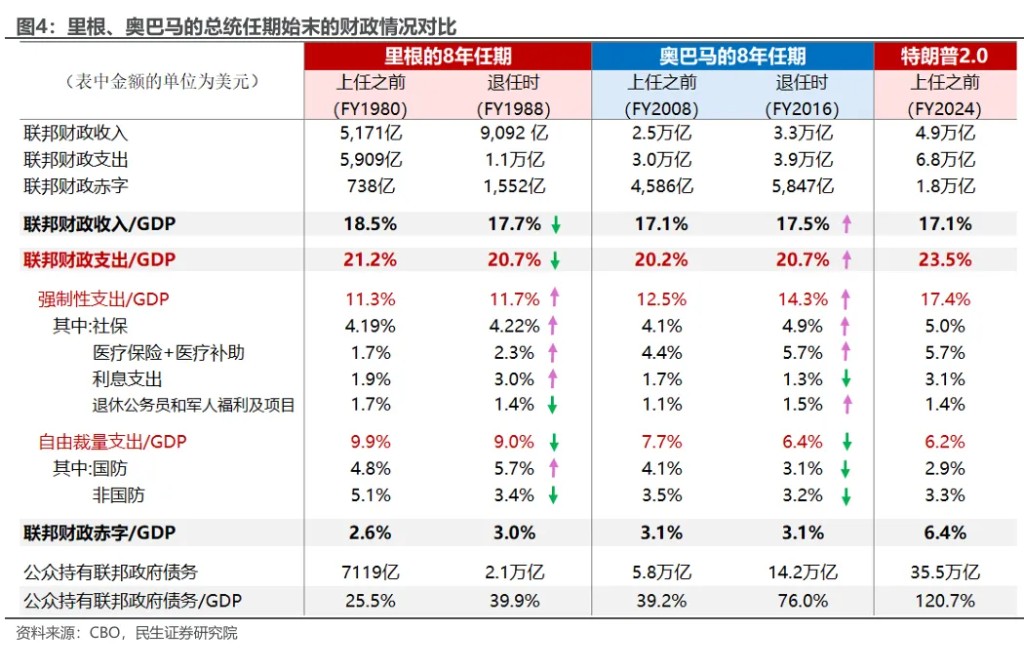

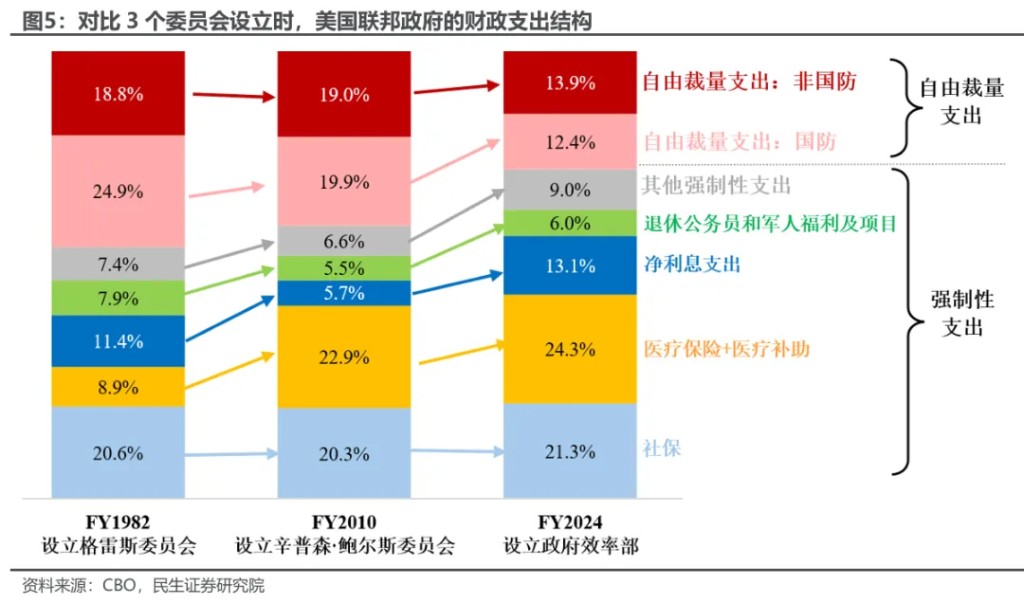

Measured by the proportion of expenditure to GDP (as shown in Figure 4), during Reagan's term, the main cuts were in non-defense discretionary spending, with reductions also in retirement benefits for civil servants and military personnel, while defense spending, social security, healthcare, and net interest expenditures increased. During Obama's term, discretionary spending and net interest expenditures decreased, while social security, healthcare, retirement benefits for civil servants, and military personnel increased.

It can be seen that "non-defense discretionary spending" has always been the "target" for cuts; retirement benefits for civil servants and veterans may also be cut; whether defense spending can be reduced depends on geopolitical relations and the international environment; while social security and healthcare expenditures are very difficult to reduce.

Looking at the current fiscal expenditure structure, there is even less room for further cuts (as shown in Figure 5): the proportion of discretionary spending in total expenditure has significantly decreased, while social security, healthcare, and medical assistance now account for 46% of total fiscal expenditure.

Historically, can the "Department of Government Efficiency" achieve its goals?

After the establishment of the Grace Commission and the Simpson-Bowles Commission, there was indeed a short-term reduction in the proportion of fiscal expenditure and deficits to GDP, and many recommendations were implemented, such as the Grace Commission's proposal to close redundant military bases and transfer federal control of two airports to local authorities, which were adopted by Congress.

However, it did not reach the initially envisioned "blueprint." Key measures for expenditure cuts often require Congressional approval, such as reforms to social security and healthcare, and reforms to the federal employee retirement system. The Grace Commission pointed out that only 27% of its proposed recommendations could be authorized by the President, while the remaining 73% required cooperation from Congress.

We expect that the final effect of the "Department of Government Efficiency" may be similar to history, namely: it can play a certain role in reducing expenditures in the short term; but it is difficult to achieve its goals. During Trump's 2.0 term, the deficit rate is indeed expected to decrease; however, the probability of achieving the proposed 3% deficit rate target and Musk's proposed $2 trillion expenditure cut is relatively low

Author of this article: Pei Mingnan S0100524080002, Tao Chuan, Source: Chuan Yue Global Macro, Original title: "Streamlining: Lessons from Musk's Predecessors (Minsheng Macro Pei Mingnan)"

Risk Warning and Disclaimer

The market has risks, and investment requires caution. This article does not constitute personal investment advice and does not take into account the specific investment goals, financial conditions, or needs of individual users. Users should consider whether any opinions, views, or conclusions in this article are suitable for their specific circumstances. Investment based on this is at one's own risk