Oaktree Capital's Marks: New things are prone to bubbles, currently PE buying the S&P 500, 10-year yield is only ±2%

Max recently released a memo titled "Revisiting the Bubble," stating that investors are currently betting that the leading high-tech companies can maintain their dominance. However, he believes that sustaining this lead is not easy, as new technologies and competitors can surpass the existing market leaders at any time. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy based on this assumption, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. He specifically pointed out the frenzy surrounding new technologies like artificial intelligence, and how this positive sentiment may spread to other high-tech sectors

Howard Marks, the founder of Oak Tree Capital, recently released his first memo of 2025 titled "On Bubble Watch," discussing the most concerning issue for U.S. stock investors: Is there a bubble in the U.S. stock market, especially among the Magnificent 7?

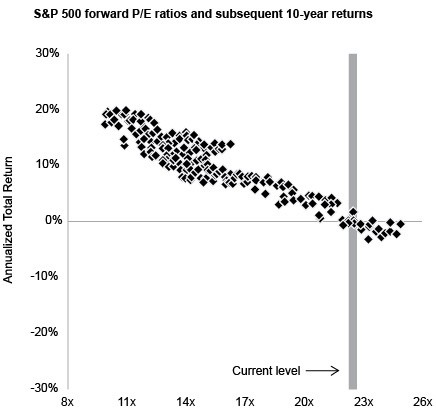

Marks pointed out that new things are prone to create bubbles. Currently, investors are betting that leading high-tech companies can maintain their lead, but he believes that sustaining that lead is not easy, as new technologies and competitors can surpass existing market leaders at any time. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy based on that, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. Historical data shows that buying the S&P 500 at the current price-to-earnings ratio would only yield a -2% to 2% return over ten years. He specifically noted the frenzy surrounding new technologies like artificial intelligence and how this positive sentiment may spread to other high-tech fields.

Wall Street Insight has summarized the core points of Marks' memo:

-

Bubbles or crashes are more of a psychological state than a quantitative calculation. When everyone believes that the future will only get better, it becomes difficult to find reasonably priced assets.

-

Bubbles are always closely linked to emerging things. If something is entirely new, it means there is no history to reference, which means there is nothing to curb the market's frenzy.

-

When something is elevated to a popular pedestal, the risk of its decline becomes very high. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy based on that, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. The optimism surrounding new things often amplifies mistakes, leading to their stock prices being assigned excessively high valuations.

-

The leading companies in the current S&P 500 index are, in many ways, far superior to the best companies of the past. They possess strong technological advantages, large scales, and dominant market shares, resulting in profit margins far above average, and their price-to-earnings ratios are not as exaggerated as during the "Nifty Fifty" era of the 1960s.

-

Currently, investors are betting that leading high-tech companies can maintain their lead. However, in the high-tech field, sustaining that lead is not easy, as new technologies and competitors can surpass existing market leaders at any time. Investors need to remember that even the best companies can lose their leading position and face significant risks when priced too high.

-

The most dangerous thing in the world is "thinking there is no risk." Similarly, because people observe that stocks have never performed poorly in the long term, they fervently buy stocks, pushing prices up to levels that will inevitably perform poorly. If stock prices rise too quickly, far exceeding the company's earnings growth rate, it is unlikely to sustain that increase.

-

Buying the S&P 500 at the current price-to-earnings ratio historically indicates a return of only -2% to 2% over ten years. If stock prices remain unchanged over the next decade while company profits continue to grow, it will gradually normalize the price-to-earnings ratio. However, another possibility is that the valuation adjustment occurs within one or two years, leading to significant declines similar to those in 1973-1974 or 2000-2002 In this case, the results are not so friendly.

Max also listed several warning signs in the market, including that market sentiment has been generally optimistic since the end of 2022; the S&P 500 index is valued above average, and most industry stocks have price-to-earnings ratios higher than their peers in other parts of the world; the frenzy over new technologies such as artificial intelligence, and this positive psychology may spread to other high-tech fields; the implicit assumption of the continued success of the "Seven Sisters" companies; index funds automatically buying these stocks, which may push up stock prices while ignoring their intrinsic value.

Here are the highlights compiled by Wall Street Insights:

In the first decade of this century, investors experienced two notable bubbles—resulting in significant losses.

The first was the internet bubble at the end of the 1990s, which began to burst in mid-2000; the second was the real estate bubble in the mid-2000s, which led to the following consequences: (a) issuing mortgage loans to subprime borrowers who could not or were unwilling to prove income or assets; (b) structuring these loans into leveraged, tiered mortgage-backed securities; (c) ultimately causing investors, especially financial institutions that created and held some of these securities, to suffer huge losses.

Due to these experiences, many people today remain highly vigilant about bubbles, and I am often asked whether there is a bubble phenomenon in the S&P 500 index and its dominant stocks.

The seven largest stocks in the S&P 500 index—known as the "Magnificent Seven"—are Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Amazon, NVIDIA, Meta (the parent company of Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram), and Tesla. In short, a few stocks have dominated the S&P 500 index in recent years and contributed an extremely disproportionate increase.

A chart from Michael Cembalest, Chief Strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management, shows:

- As of the end of October, the seven largest companies in the S&P 500 index accounted for 32% to 33% of the total market capitalization of the index;

- This proportion is about twice that of the leading companies five years ago;

- Before the rise of the "Seven Sisters," the highest record of the proportion of the top seven stocks over the past 28 years was around 22% during the peak of the TMT bubble in 2000.

Another important data point shows that as of the end of November, U.S. stocks accounted for more than 70% of the MSCI Global Index, the highest proportion since 1970, also from Cembalest's chart. Therefore, it is clear that: first, the market capitalization of U.S. companies is very high compared to companies in other regions; second, the value of the seven largest U.S. companies is even more prominent relative to other U.S. stocks.

But is this a bubble?

A Bubble is More of a Psychological State

In my view, a bubble or crash is more of a psychological state than a quantifiable calculation. A bubble not only reflects a rapid rise in stock prices but also manifests as a temporary frenzy characterized by—or more precisely, caused by the following factors:

Highly irrational optimism (borrowing the term "irrational exuberance" from former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan);

Extreme admiration for relevant companies or assets, along with the belief that they cannot fail;

Fear of missing out (FOMO), worrying about being left behind for not participating;

The resulting belief that "there is no price too high" for these stocks.

To identify a bubble, one can look at valuation metrics, but I have long believed that psychological analysis is more effective. Whenever I hear "there is no price too high" or similar statements—even when more cautious investors say, "Of course, prices could be too high, but we are not there yet"—I take it as a clear signal that a bubble is brewing.

About fifty years ago, a mentor gave me one of my favorite maxims. I have written about it in several memos, but I think it bears repeating. It is "the three stages of a bull market":

The first stage usually occurs after a market decline or crash, when most investors are disheartened and battered, and only a few sharp-eyed individuals can envision a future improvement.

In the second stage, the economy, companies, and markets perform well, and most people begin to accept that conditions are indeed improving.

The third stage, after continuous positive economic news, significant earnings reports from companies, and soaring stock prices, leads everyone to believe that the future can only get better.

What matters is not the actual performance of the economy or companies, but the psychology of investors. This is not about what is happening in the macro world, but how people perceive these developments. When few believe that conditions will improve, security prices clearly do not incorporate much optimism. But when everyone believes that the future can only get better, it becomes difficult to find reasonably priced assets.

New things spark the creation of bubbles

Bubbles are always closely tied to new phenomena. The "Nifty Fifty" stock bubble in the U.S. in the 1960s, the disk drive company bubble in the 1980s, the internet bubble at the end of the 1990s, and the subprime mortgage-backed securities bubble from 2004 to 2006 all followed similar trajectories.

Under normal circumstances, if a particular industry or country's securities attract abnormally high valuations, investment historians often point out that in the past, the valuation premium of these stocks has never exceeded a certain percentage of the average level or provide other similar indicators. The reference of history acts like a tether, keeping the sought-after group of stocks grounded in reality, preventing them from flying too far.

But if something is entirely new, meaning there is no history to reference, then there is nothing to curb the market's frenzy. After all, these stocks are owned by the smartest people—those star investors who frequently appear in headlines and on television, and they have made a fortune. Who would want to throw cold water on such a festive occasion or refuse to join the dance? Like "The Emperor's New Clothes," the con artist sells the emperor a magnificent outfit that supposedly only smart people can see, but in reality, there are no clothes at all. When the emperor parades naked through the town, the citizens are afraid to admit they can't see the clothes because that would make them seem not smart enough.

In the investment market, most people would rather go with the flow, accepting this shared illusion that can make investors rich quickly, than stand up and voice dissent, risking being seen as a "fool." When the entire market or a certain class of securities skyrockets, and a baseless notion allows believers to make a fortune, few dare to risk exposing the truth.

Buying the "Nifty Fifty" once lost 90%

I joined the equity research department of First National City Bank (now Citibank) in September 1969. Like most so-called "money center banks," Citibank primarily invested in the "Nifty Fifty," stocks considered to be the best and fastest-growing companies in America. These companies were thought to be so good that they would never have problems, and their stocks were deemed to have no "overvaluation."

Investor obsession with these stocks stemmed from three factors. First, the U.S. economy experienced strong growth after World War II. Second, these companies were involved in innovative fields such as computers, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods. Third, they represented the first wave of "growth stocks," a new style that later became fashionable in investing.

Thus, the "Nifty Fifty" became the first major bubble in 40 years, and since investors had not experienced a bubble for a long time, they had long forgotten what a bubble looked like. Therefore, on the day I started working, buying these stocks and holding them for five years resulted in a loss of over 90% of funds in these top American companies. What happened?

The "Nifty Fifty" was revered, and when something falls from grace, investors get hurt. Between 1973 and 1974, the entire stock market fell by about half. It turned out that the prices of these stocks were indeed outrageous; in many cases, their price-to-earnings ratios fell from the range of 60-90 times to 6-9 times (this is the simple calculation of losing 90% of assets). Additionally, from a fundamental perspective, several of these companies did encounter actual bad news.

A real bubble I experienced early on led me to summarize some guiding principles that have benefited me greatly over the next 50 years:

The key is not what you bought, but how much you paid.

Excellent investing does not come from buying good assets, but from buying assets at good prices.

No asset is so good that it cannot be overvalued to the point of becoming dangerous, nor is any asset so bad that it cannot become cheap enough to be a bargain.

The higher you hold, the harder you fall

The bubbles I have experienced all involved innovation, as mentioned earlier, many of which were either overvalued or not fully understood. The allure of new products or business models is often obvious, but the traps and risks are often hidden, only to be revealed in difficult times.

A new company may completely surpass its predecessors, but inexperienced investors often overlook that even the most dazzling new star can be replaced. Disruptors themselves can also be disrupted, whether by more skilled competitors or newer technologies In my early business career, technology seemed to develop gradually. But by the 1990s, innovation suddenly accelerated. Oak Tree Capital was founded in 1995, at a time when investors firmly believed that "the internet would change the world." This view seemed very reasonable and led to a huge demand in the market for everything related to the internet. E-commerce companies went public at seemingly high prices, with stock prices tripling on the first day, sparking a real gold rush.

When something is elevated to the altar of popularity, the risk of its decline becomes very high. When people assume that "things will only get better" and buy accordingly, the impact of negative news can be particularly severe. The optimism surrounding new things often further amplifies mistakes, leading to their stock prices being assigned excessively high valuations.

As mentioned earlier, for new things, there is a lack of historical data to measure reasonable valuations.

Moreover, the potential of these companies has not yet translated into stable profits, which means that valuations are essentially guesses. During the internet bubble, these companies were not profitable, so the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio was out of the question. As startups, they often had no revenue at all, so investors had to invent new metrics—such as "clicks" or "eyeballs"—and whether these metrics could translate into revenue and profit was completely unknown.

Because bubble participants cannot imagine any potential risks, they often assign valuations assuming that success is certain.

In reality, investors even tend to view all competitors in new fields as potentially successful, while in reality, only a few companies can truly survive or succeed.

Ultimately, in hot new things, investors often adopt what I call a "lottery mentality." If a successful startup in a hot field can bring a 200-fold return, even if it has only a 1% chance of success, it is mathematically worth investing. So, what doesn't have a 1% chance of success? When investors think this way, they almost never limit their investments or the prices they are willing to pay.

Clearly, investors can easily get caught up in the race to buy the latest hot thing, which is precisely why bubbles form.

What is the right price to pay for a bright future? Being ahead is actually rare.

If there is a company expected to earn $1 million next year and then shut down, how much would you be willing to pay to buy it? The correct answer is slightly less than $1 million, so you can achieve a positive return.

But stocks are usually priced based on the "price-to-earnings ratio," which is a multiple of the company's expected earnings for the next year. Why? Because people assume that the company will not just be profitable for one year, but will continue to be profitable for many years. When you buy a stock, you are essentially buying a share of the company's future earnings each year.

However, the current value of a company is actually the present value of its future earnings discounted at a certain rate. Therefore, a P/E ratio of 16 actually means you are paying for more than 20 years of earnings (depending on the discount rate applied to future earnings).

During bubble periods, the trading prices of hot stocks are far above a P/E ratio of 16. For example, the P/E ratio of the "Nifty Fifty" stocks once reached as high as 60 to 90 times! Investors in 1969, when paying these high prices, even considered profit growth for the coming decades So, were they consciously and analytically calculating this valuation? I don't remember such a situation. At that time, investors simply treated the price-to-earnings ratio as just a number.

So are today's market leaders different? The leading companies in the current S&P 500 index are, in many ways, far superior to the best companies of the past. They possess strong technological advantages, massive scale, and dominant market shares, resulting in profit margins well above average. Additionally, because these companies' products rely more on "creativity" rather than physical goods, the marginal cost of producing additional units is lower, which means exceptionally high marginal profitability.

More notably, the price-to-earnings ratios of today's market leaders are not as exaggerated as during the "Nifty Fifty" era. For example, Nvidia, regarded as the "sexiest" company and a leading designer of AI chips, has a price-to-earnings ratio of about 30 times. Although this price-to-earnings ratio is twice the post-war average for the S&P 500 index, it still appears cheap compared to the "Nifty Fifty."

However, what does a price-to-earnings ratio of over 30 mean? First, investors believe that Nvidia will continue to operate for decades to come; second, investors believe that its profits will continue to grow over the next few decades; third, they assume that Nvidia will not be replaced by competitors. In other words, investors are betting that Nvidia can maintain its sustained leadership.

But in the high-tech field, maintaining sustained leadership is not easy, as new technologies and competitors can potentially surpass existing market leaders at any time. For example, according to the "Nifty Fifty" list on Wikipedia, only about half of the companies are still in the S&P 500 index today.

Once-star companies like Xerox, Kodak, Polaroid, Avon, Burroughs, Digital Equipment, and Simplicity Pattern are no longer part of the S&P 500 index.

According to finhacker.cz, at the beginning of 2000, the 20 largest companies by market capitalization in the S&P 500 index were:

-

Microsoft

-

Merck

-

General Electric

-

Coca-Cola

-

Cisco Systems

-

Procter & Gamble

-

Walmart

-

AIG

-

Exxon Mobil

-

Johnson & Johnson

-

Intel

-

Qualcomm

-

Citigroup

-

Bristol-Myers Squibb

-

International Business Machines (IBM)

-

Pfizer

-

Oracle

-

AT&T

-

Home Depot

-

Verizon

However, by early 2024, only 6 of these companies remained in the top 20:

-

Microsoft

-

Johnson & Johnson

-

Walmart

-

Procter & Gamble

-

Exxon Mobil

-

Home Depot

More importantly, among today's "Magnificent Seven," only Microsoft was in the top 20 twenty-four years ago.

Therefore, during the bubble period, investors had extremely high expectations for leading companies and were willing to pay a premium for their stocks, as if these companies were destined to continue leading for decades to come. However, the reality is often that change is more common than continuity. Investors need to remember that even the best companies can lose their leading position and face significant risks when priced too high.

The Most Dangerous Belief is "There is No Risk"

The most severe bubbles often originate from innovation, primarily in technology or finance, initially affecting only a small number of stocks. But sometimes, this bubble can extend to the entire market, as the enthusiasm for one bubble sector spreads to all areas.

For example, in the 1990s, the S&P 500 index was driven by two main factors: first, the continuous decline in interest rates that peaked in the early 1980s to combat inflation; second, investors reignited their enthusiasm for stocks, which had once disappeared after the traumas of the 1970s. The technological innovations and rapid profit growth of high-tech companies further fueled this enthusiasm.

At the same time, new academic research shows that the S&P 500 has never historically underperformed bonds, cash, or inflation in the long term. These positive factors combined to give the index an average annual return of over 20% in the 1990s. I have never seen a period like that.

I often say, the most dangerous thing in the world is "to believe there is no risk." Similarly, because people observe that stocks have never underperformed in the long term, they fervently buy stocks, pushing prices to levels that will inevitably underperform. In my view, this reflects George Soros's theory of investment "reflexivity."

After the internet bubble burst, the S&P 500 index fell for three consecutive years in 2000, 2001, and 2002, marking the first three-year decline since the Great Depression of 1939. Due to poor market performance, investors massively sold off stocks, resulting in a cumulative return of zero for the S&P 500 index from the 2000 bubble peak to December 2011, lasting over 11 years Recently, I often quote a saying that I believe was said by Warren Buffett: "When investors forget that a company's profit growth rate is about 7% per year, they often get into trouble." This means that if a company's profits grow by 7% each year, but the stock price rises by 20% annually in the short term, the stock price will ultimately be high and fraught with risk.

The key is that if the stock price rises too quickly, far exceeding the company's profit growth rate, it is unlikely to sustain that increase.

A chart provided by Michael Semblareste illustrates this point well. The data shows that prior to the last two years, the S&P 500 index had only four instances of consecutive two-year increases of over 20%. In three of these four instances, there was a decline in the following two years. (The only exception was from 1995 to 1998, when the tech bubble strongly propelled the market, delaying the decline until 2000, but subsequently, the index fell nearly 40% over three years).

In the past two years, this has happened for the fifth time. The S&P 500 index rose 26% in 2023 and 25% in 2024, marking the best two-year performance since 1997-1998. So what will happen in 2025?

Current Market Warning Signals

Here are several signs to be wary of at present:

- The market has been generally optimistic since the end of 2022;

- The S&P 500 index is valued above average, and most industry stocks have price-to-earnings ratios higher than their peers in other regions of the world;

- The frenzy over new technologies like artificial intelligence, and this positive sentiment may spread to other high-tech fields;

- The implicit assumption of the continued success of the "Magnificent Seven" companies;

- Index funds automatically buying these stocks may push up prices while ignoring their intrinsic value.

Additionally, although not directly related to the stock market, I must mention Bitcoin. Regardless of whether its value is reasonable, it has risen 465% in the past two years, which does not indicate an excess of caution in the market.

On the eve of releasing this memo, I received a chart from JP Morgan Asset Management. This chart shows monthly data from 1988 to 2014 (a total of 324 months), reflecting the relationship between the S&P 500's price-to-earnings ratio at that time and the subsequent ten-year annualized returns.

The following points are noteworthy:

There is a significant correlation between initial valuations and subsequent ten-year annualized returns: the higher the starting valuation, the lower the subsequent returns, and vice versa.

The current price-to-earnings ratio is clearly in the top 10% of historical data.

During this 27-year period, when the S&P 500's price-to-earnings ratio was around the current level of about 22 times, the subsequent ten-year return rates ranged between +2% and -2%. Some banks have recently predicted that the return on the S&P 500 over the next decade will be in the low to mid-single digits. Therefore, investors clearly should not overlook the current market valuations.

Of course, you might say, "A return of ±2% over the next decade isn't too bad." Indeed, if stock prices remain unchanged over the next decade while company profits continue to grow, it would gradually bring the price-to-earnings ratio back to normal levels. But another possibility is that the valuation adjustment could occur within one or two years, leading to significant declines similar to those seen in 1973-1974 or 2000-2002. The outcome in such a case would be less friendly.

Of course, there are also some counterarguments to the view that the current market is overvalued, including:

- The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 is high, but not excessively so;

- The "Seven Sisters" are very strong companies, so their high price-to-earnings ratios may be justified;

- I haven't heard people say "the higher the price, the better";

- Although the market is priced high and may even have some bubbles, it is still relatively rational overall.

I am not a stock investor, nor am I a technical expert. Therefore, I cannot authoritatively determine whether we are in a bubble. I am simply listing the facts as I see them and suggesting how you might think about these issues