What does a decrease in the U.S. unemployment rate to 4.1% mean?

美國失業率下降至 4.1%,反映出 2024 年下半年勞動力市場的變化。儘管經歷了颶風的影響,市場對經濟的預期從衰退轉向不着陸。聯儲的政策也在快速調整,關注點從通脹轉向就業。12 月的非農報告顯示新增就業強勁,失業率回落,進一步引發對再通脹的擔憂。整體來看,經濟波動是常態,需關注主要矛盾和關鍵變量。

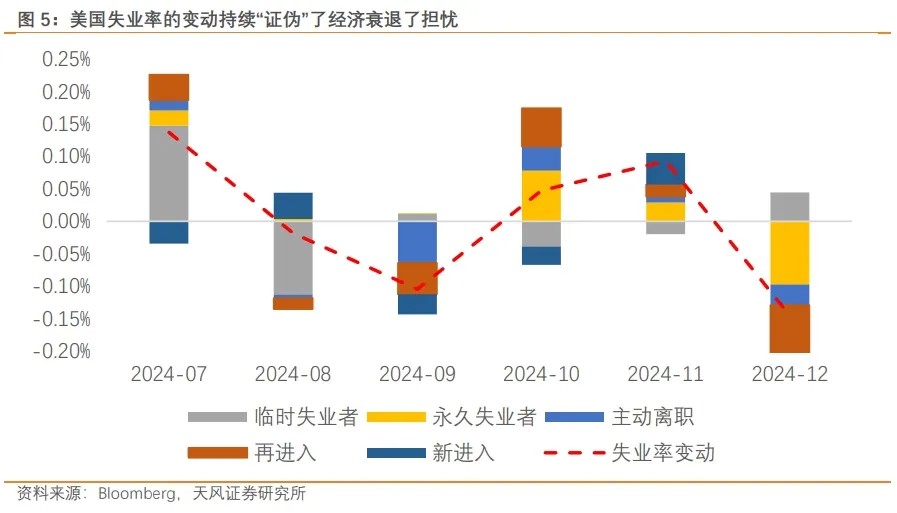

在 12 月美國非農公佈後,可以較為清晰地勾勒出 2024H2 美國勞動力市場的演進:失業率伴隨着兩場颶風起起伏伏,導致市場預期從 7 月的 “衰退有多深 (how deep)” 再次擺動回了美國經濟 “不着陸 (no landing)”。與之相對的是聯儲參考系的快速變動:從通脹到就業,現在又回到了通脹。

標題中的 “友好討論” 是對 7 月非農報告的呼應(《關於 4.3% 失業率的 “友好討論”》),當時失業率在颶風擾動的下出現了非線性跳升,但我們依然認為彼時衰退風險的計入過度極端。反而在看到聯儲 9 月 “超預期” 降息 50bp 後,隨後強勁的非農報告又足以讓我們更加重視失業率的下行風險,以及需求端的二次通脹風險(《非農強化二次通脹風險》)。

從結果看,得到逐步的印證:2024H2 的失業率走出波動下行的態勢,7 月反而成為最高點;而去通脹進程則面臨明顯停滯,核心 CPI 連續處在 0.3% 左右水平。波動本就是經濟的常態,對待美國經濟更應該揣着 “波瀾不驚” 的態度,抓住主要矛盾和更有解釋力度的變量。

站在 “友好討論” 的視角下:迄今為止,本輪週期中就業和失業的脱節使得我們更應該關注(壯年)就業率的表現,而薪資增速粘性的維持也推動了美國消費(以及 GDP)的持續增長,聯儲降息就更加顯得過度。

回到 12 月非農報告,即使此前聯儲官員對 2025 年降息預期的鷹派吹風,此次數據依然顯得極為強勁(25.6 萬人,預期 16.5 萬人)。高增的私人服務新增就業(23.1 萬人)以及回落的失業率(4.086%)一掃對於非農擔憂的陰霾,足以將聯儲的關注度再次完全擰回對再通脹擔憂。

尤其是聯儲 12 月 SEP 中沒有任何一位官員認為失業率會回落至 4.1% 水平(集中在 4.2%-4.3%),但依然選擇再次降息 25bp,這又進一步放鬆了利率對於就業的限制程度。

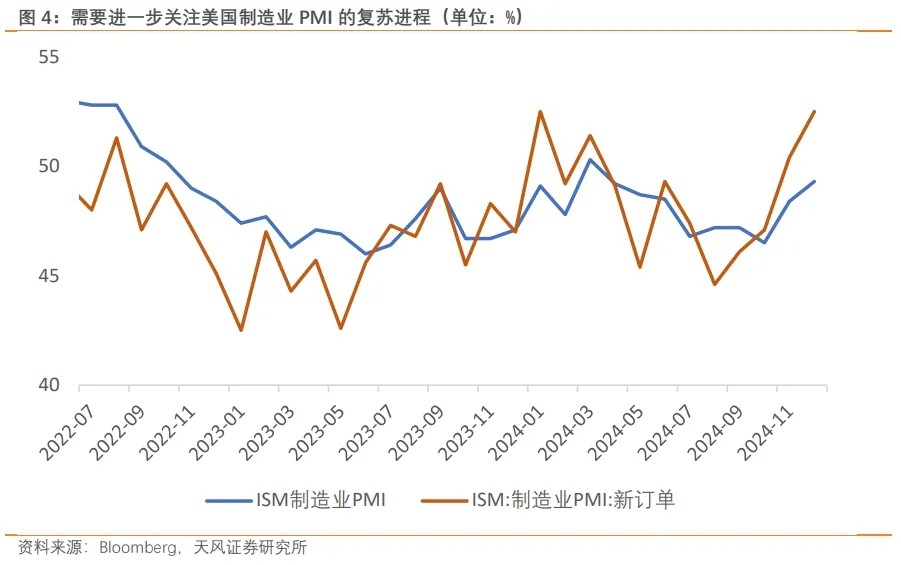

本次報告中唯一的 “結構性瑕疵” 來自於製造業就業並未見起色,甚至錄得負增長水平(-0.8 萬人)。但這也説明高利率不是製造業的唯一約束,在高庫存、貴人工(製造業薪資較高)的約束下,製造業修復幅度有限(PMI 雖小幅反彈,但依然低於 50 水平;但製造業新訂單 PMI 再度升破 50 水平)。

如果製造業就業也持續修復,我們更應重視非農過強(失業率下行)的風險,映射到 2025 年貨幣政策,可能就不是降息多少/與否,而是討論 2025H2 的加息可能。

私人服務業的趨勢性修復意味着,100bp 的降息幅度加強了本就受利率影響不大的薪資 - 消費 - 通脹的循環,尤其是異常高增的貿易交運(4.9 萬人)本質上也印證了感恩節較強的美國消費需求,至少 12 月的零售與服務相關的通脹數據是存在較熱的風險。

失業率的再度下行(4.086%)伴隨着勞動參與率的走平説明了一個事實:對於失業率非線性上升的擔憂是錯誤的,而聯儲基於此的 100bp 降息也帶來了利率的過度放鬆。無論是 2024 年 9 月還是 12 月,美國失業率本身就不應該成為聯儲貨幣政策目標中被 “偏愛” 的那個。

最後,薪資增速的粘性(0.3% 的環比)推動居民實際購買力的持續回升。降息週期中,美國服務業被持續強化。從基本面的角度,我們並不擔心美國服務業的走弱的下行風險,反之,更需要關注製造業在未來數月是否可能出現上行風險。這將是除特朗普對內改革以外最重要的預期差變量。

非農的強趨勢面臨的最大阻力或來自非經濟因素:包括特朗普上任後反移民措施力度的不可預知性,以及非法移民從紅州向藍州遷移,甚至有被迫離開美國的可能。從短期來看,這可能成為非農最大的擾動與下行來源。

對於特朗普來説,如此強勢的經濟開局或並不會帶來很大的 “壓力”,畢竟他沒有明面上的連任訴求;反而更可能給他吃下了一顆強力改革的 “定心丸”。“天時(再度當選總統),地利(經濟數據強勁),人和(四權在手)” 的基礎上,特朗普的改革或更大膽,而站在勞動力市場的角度意味着短期受到非經濟因素的更大擾動的風險。

從聯儲的角度看,特朗普和鮑威爾為數不多的共識就是避免美國經濟真的衰退,如此強勁的非農提供了很厚的擾動緩衝墊。

隨着特朗普當選後,“強預期” 的破滅可能(《美元的強勢能否維持》),疊加美國經濟在改革和爭議法案推進下或將變得更加混亂,聯儲將在 2025H1 選擇繼續降息;但到了 2025H2,內生動能的保持和 “避免美國陷入實質性衰退” 的訴求,將明顯推升 2025H2 加息的可能。

本文作者:宋雪濤 S1110517090003、鍾天,文章來源:雪濤宏觀筆記,原文標題:《關於失業率 4.1% 的再次 “友好討論”(天風宏觀鍾天)》

風險提示及免責條款

市場有風險,投資需謹慎。本文不構成個人投資建議,也未考慮到個別用户特殊的投資目標、財務狀況或需要。用户應考慮本文中的任何意見、觀點或結論是否符合其特定狀況。據此投資,責任自負。