After the bull market, fund managers who manage $100 trillion in assets are facing challenges.

According to data from Boston Consulting Group, since 2006, approximately 90% of the additional revenue for fund management companies has come from the continuously rising market, rather than the ability to attract new client funds.

In just two years, Puxin Group has experienced a capital outflow of $127 billion. The latest billionaire family member to take control of the company at Franklin Resources is trying to reverse nearly 20 consecutive quarters of losses. Across the Atlantic, the CEO of Abrdn Plc has come to a straightforward conclusion: managing mutual funds alone is no longer enough.

Zhitong Finance APP noticed that in the $100 trillion asset management industry, fund managers have faced a structural shift in investor preference for cheaper, passive strategies over the past decade. Now, they face an even more daunting situation: the unprecedented bull market that has supported their investments and masked vulnerabilities threatening their survival may be a thing of the past.

Data from Boston Consulting Group shows that since 2006, about 90% of additional revenue for fund management companies has come from rising markets rather than the ability to attract new client funds. Many senior executives and consultants are now warning that it won't take much time to turn the industry's slow decline into a cliff edge moment: another bear market, and many of these companies will find themselves unable to recover.

Ben Phillips, Head of Asset Management Global Consulting at Broadridge Financial Solutions, said, "This is the last step for many companies that have been smooth sailing for decades. These companies must change, and they must succeed in doing so."

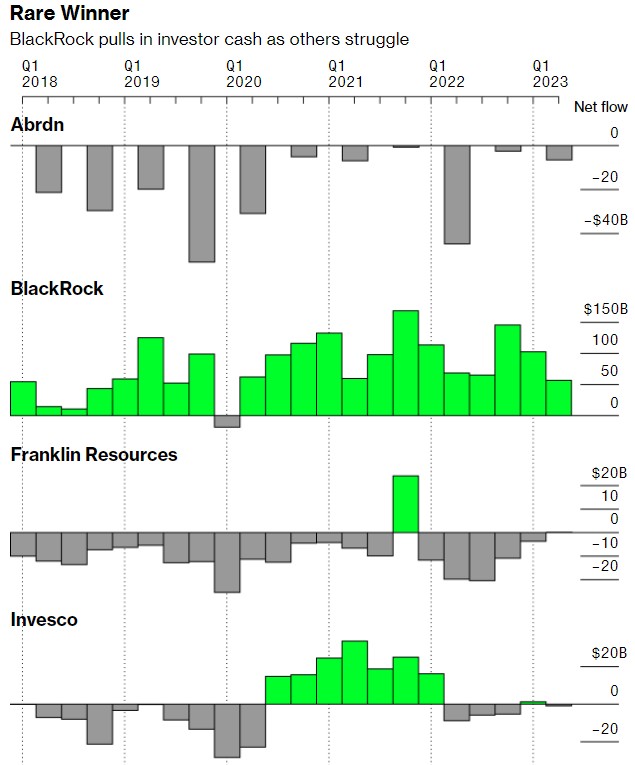

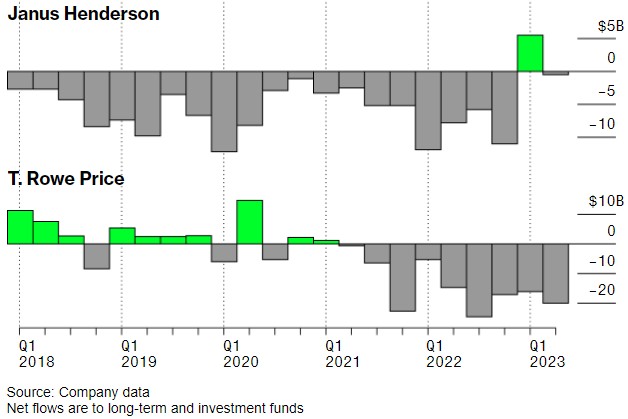

Since 2018, over $600 billion in client funds has been withdrawn from Puxin Group, Franklin Resources, Abrdn, Janus Henderson Group Plc, and Invesco's investment funds. This is more than all the funds regulated by Abrdn, one of the UK's largest independent asset management companies. Using these five companies as examples, they are now trying to prove that their business is the right one after losing a significant amount of client funds over the past decade.

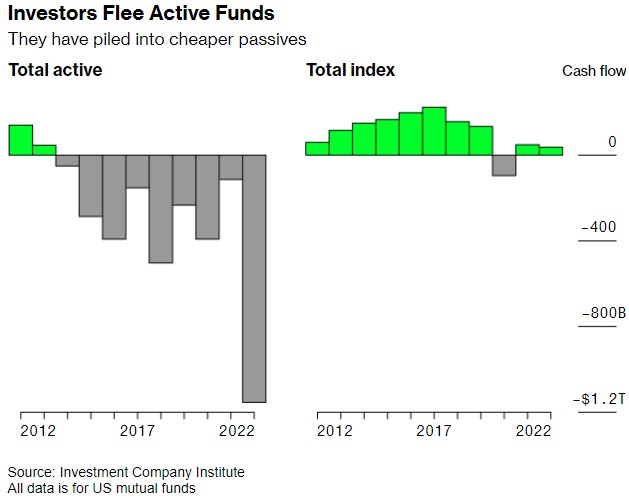

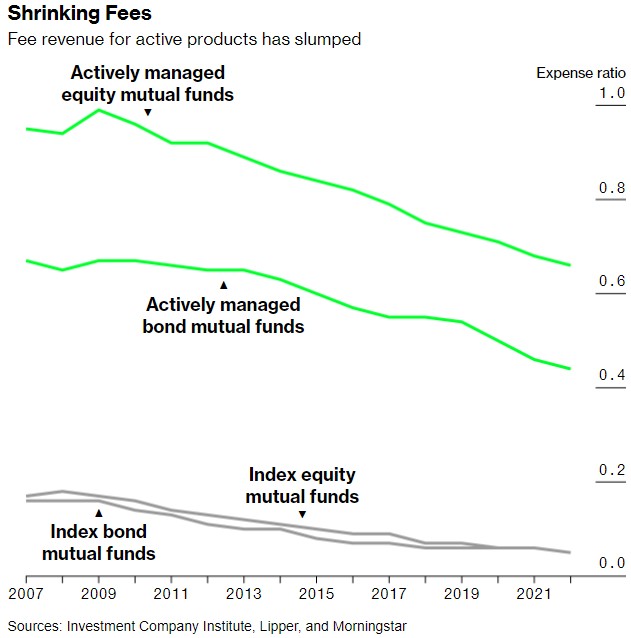

The reasons for these companies' predicament are no secret: investors are abandoning mutual funds and turning to much lower-cost passive strategies, mainly managed by giants such as BlackRock, Vanguard Group, and JPMorgan Chase, which has led to significant fee compression in the entire industry and put pressure on the revenue and profit margins of smaller fund companies.

As geopolitical tensions and rising interest rates become the norm, even the $9.1 trillion giant BlackRock is feeling some pain. In the three months ending in September, clients withdrew a net $13 billion from its long-term investment funds, marking the first outflow of funds of this kind since the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020.

As geopolitical tensions and rising interest rates become the norm, even the $9.1 trillion giant BlackRock is feeling some pain. In the three months ending in September, clients withdrew a net $13 billion from its long-term investment funds, marking the first outflow of funds of this kind since the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020.

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink told analysts this month that "structural and long-term changes in business models, technology, especially in monetary and fiscal policies, have posed significant challenges to traditional asset management over the past two years."

Bloomberg analyzed the fund flows, expenses, investment performance, revenue, and profit margins of these five companies over the past five years, as well as the trends in the entire industry, showing that active fund managers face greater risks than ever before. As of June 30, these five listed companies managed over $5 trillion in assets, from workers participating in 401(k) plans to the world's largest pension funds, and have been well-known names in the global asset management field for decades. They were selected as representatives of the middle tier of asset management, which is now under tremendous pressure, while most other participants in the industry are struggling.

The stock prices of these five companies indicate the state of the game. Except for Aberdeen, since early 2018, the market value of all these companies has fallen by at least one-third, while the S&P 500 index has risen by about 60%. Except for Abrdn, which releases earnings reports every six months, these companies will announce their quarterly earnings reports in the next two weeks, starting on Tuesday when Schroders will release its quarterly earnings report.

Although they hope that when times get tough, clients will reselect stocks and bonds - and pay for it - the downward trend seems irreversible. According to data collected from asset management companies, passive products have gained such great appeal regardless of whether the market is rising or falling. By mid-year, passive products accounted for half of the total assets of U.S. mutual funds and ETFs, surpassing 47% in 2022 and 44% in 2021. Ten years ago, this proportion was only 27%.

It seems that the struggle against index machines is not enough, and now there is a new enemy: cash. In the case of persistently high interest rates, investors want to keep their money in cash.

Previous generations of CEOs have tried countless times to reverse the situation: they cut costs (resulting in only a decrease in revenue), merged with competitors (creating more problems than solving them), and embraced various trends such as ESG, hoping to gain an advantage (resulting in looking more like competitors rather than differentiating from them). Without exception, these attempts have been ineffective. Now, a new group of bosses in the active management field, including Rob Sharps from PIMCO, Andrew Schlossberg from Invesco, Ali Dibadj from Janus, Stephen Bird from Abrdn, and Jenny Johnson from Franklin, are poised to turn the tide. The new CEOs include both seasoned insiders and external hires brought in to restructure the companies. They are dealing with the seemingly shrinking legacy businesses that have been contracting month after month, as well as the increasingly urgent need to expand their core businesses beyond traditional actively managed mutual funds.

Stefan Hoops, CEO of DWS, the asset management arm of Deutsche Bank, said, "Over the past 10 years, more than 100% of revenue growth has been driven by market performance—it's just that the market has been going up." DWS, a $900 billion asset management company under Deutsche Bank, took over the company last year and has been investing in ETFs and alternative investment funds to cope with the pressure. "Now imagine if the market is flatlining, but profit margins are compressed to the same extent, suddenly you could be facing a decade of revenue decline."

Since 2018, Franklin has only had two quarters of long-term net inflows, even after periods of market activity and acquisitions. Janus Henderson, after experiencing 21 consecutive quarters of outflows, saw net inflows in the first quarter of this year, only to see outflows again shortly after. Abrdn, since its creation through a merger in 2017, has yet to experience a year of net inflows. Since mid-2021, PIMCO's funds have seen outflows of billions of dollars, with management fee income declining by over 15%. Invesco has seen little revenue growth in the past three years.

Meanwhile, BlackRock, the dominant player in the global asset management industry, has assets that are nearly twice the total assets of these five companies combined. From early 2018 to mid-year, the net inflow of its long-term investment funds totaled $17 trillion.

Evan Skalski, Deputy Director of Alpha FMC, said, "Intermediaries cannot naturally grow in this situation." Alpha FMC provides consulting services to the top 20 global asset management companies. "They can try to control costs and maintain the operation of their current businesses, but they must accept a low-growth or zero-growth story."