Wall Street is guessing: Will the Federal Reserve delay the December FOMC meeting to wait for more employment data?

The December FOMC meeting will be held before the key employment reports in October and November. UBS pointed out that this has led the market to begin discussing a possibility: whether the Federal Reserve will postpone the originally scheduled meeting on December 10 by a week to better understand the key employment data before making a decision. There have been precedents for meeting postponements in history, and the internal disagreements within the Federal Reserve regarding a rate cut in December have also heightened the importance of the timing of the meeting

The schedule for the Federal Reserve's December FOMC meeting is becoming a hot topic of discussion on Wall Street.

On November 24th, according to news from the Chase Trading Desk, UBS stated in its latest research report that the timing of the Federal Reserve's December meeting is facing an unprecedented dilemma: the FOMC meeting originally scheduled for December 9-10 will take place before the release of two key employment reports, which are crucial data for deciding whether to cut interest rates. This has prompted the market to begin discussing the possibility: will the Federal Reserve postpone the meeting originally scheduled for December 10 by a week to obtain key employment data before making a decision?

The report states that this scheduling conflict arises from delays in data releases due to the government shutdown. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has announced that the November employment report will be delayed until December 16, and will also include the previously skipped October employment data. This means that if the meeting goes ahead as planned, the FOMC will only be able to make interest rate decisions based on September employment data.

Historical precedents show that meeting adjustments are not impossible. In 1971 and 1974, the Federal Reserve postponed meetings due to special circumstances. From a regulatory perspective, the Federal Reserve Act only requires the FOMC to hold at least four meetings a year and does not impose rigid regulations on date adjustments. The current arrangement for December 9-10 is already the earliest since 2003, and even if postponed to December 16-17, it would still be within historical norms.

UBS pointed out that historically, a single employment report has been sufficient to change the direction of monetary policy, and this time the FOMC faces the risk of missing two reports. Additionally, there is currently a divergence within the committee regarding a rate cut in December, with some members supporting a further cut of 25 basis points, while "a few" believe there is no need to act in December. This also increases the importance of the timing of the December meeting.

The report notes that postponing the meeting will increase policy uncertainty but may improve decision quality. UBS maintains its forecast for a 25 basis point rate cut in December but acknowledges the risk of pausing the rate cut.

The Dilemma of Mismatched Data Releases and Decision Windows

The report states that the core of the dispute lies in the misalignment of the meeting time and the release of key data. The two non-farm employment reports for October and November, set to be released on December 16, will just miss the conclusion of the FOMC meeting on December 10. This creates a significant information blind spot for decision-makers.

UBS pointed out that the September employment data has already shown a significant weakening in the labor market. Private sector employment only grew by 97,000, and after excluding the healthcare and social assistance sectors, the four-week moving average of employment growth was negative 13,000. This data has raised market concerns about the downside risks in the labor market.

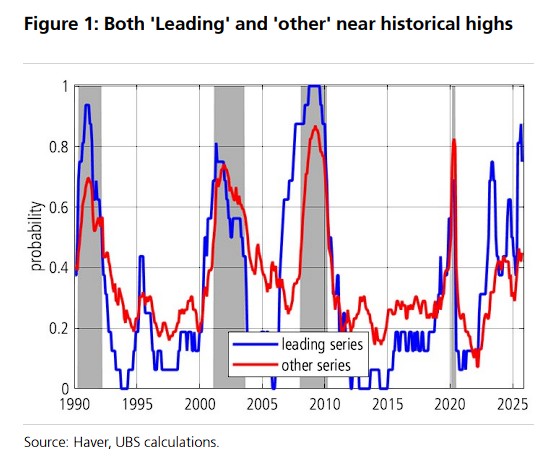

The report states that the bank's latest leading labor market indicator reached 75% in September, down from 88% in August (the highest level since the financial crisis), but still remains at historically high levels. This indicator is based on private non-farm employment data by sector and assesses the probability of recent net job losses

Data from September shows that 12 out of 16 leading industries are experiencing contraction, and the decline is continuing to widen. Excluding the healthcare sector, private employment growth remains negative on a four-month moving average basis, reaching -133,000.

Specifically, cyclical industries such as manufacturing, construction, and professional services continue to be weak. The leisure and hospitality sector improved in September, but the healthcare sector, which has been a major support for employment growth, is losing momentum. UBS pointed out that when employment growth is concentrated in non-cyclical sectors like healthcare, it is often a precursor to an economic slowdown.

UBS stated that the Federal Reserve has historically been highly sensitive to employment data, with individual employment reports having changed policy paths multiple times, with interest rate adjustments ranging from 0 to 50 basis points. Today, facing two delayed key reports, making decisions without complete data may increase the risk of policy misjudgment. The Federal Reserve has previously made it clear that formulating policy in the absence of official data is like "navigating in a fog."

UBS indicated that if they can wait for the two employment reports to be released on December 16, policy-making will be more grounded. Compared to the November CPI data, which is also delayed until December 18, information from the labor market is more critical for current decision-making. Federal Reserve officials have repeatedly emphasized that the downside risks in the labor market are central to current policy considerations.

Historical Precedents Provide Possibility for Adjustment

The report states that although the FOMC meeting schedule is usually quite fixed, there are historical precedents for adjustments, providing reference for potential changes in the December meeting schedule.

In 1971, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns postponed the May meeting by a week due to protests related to the Vietnam War. In January 1974, the meeting was postponed from the 15th to the 22nd to accommodate the schedule of an international conference, and the subsequent February meeting was also postponed accordingly to maintain a four-week interval.

In addition to postponements, the Federal Reserve has also increased the number of meetings based on emergencies multiple times. During the 2008 financial crisis, emergency meetings were held intensively, and in March 2020, five emergency meetings resulted in a cumulative interest rate cut of 250 basis points, demonstrating the flexibility of meeting arrangements.

From a legal framework perspective, according to the Federal Reserve Act, there are no explicit regulations on the meeting schedule, only requiring that "committee meetings shall be held in Washington, D.C., at least four times a year at the call of the Chairman of the Board or at the request of any three members." The rules of the Federal Open Market Committee also have similar statements.

The current meeting dates of December 9-10 are the earliest since 2003. Even if postponed by a week to the 16th-17th, it would still fall within the conventional timeframe for December meetings historically, without causing procedural conflicts or violating established rules

The Importance of Timing Selection Amidst Increasing Divergence Among Committee Members

The internal policy divergence within the Federal Reserve regarding a rate cut in December makes the timing of the meeting even more significant. According to an article from Wall Street Insight, the differing opinions reflected in the minutes of the October FOMC meeting have continued to manifest in recent statements from officials.

Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller explicitly supports a 25 basis point rate cut in December, citing that core inflation is close to the target and the labor market is weak. This position represents the camp that favors continuing accommodative policies.

However, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester holds a more cautious stance, expressing concerns that a rate cut could prolong the inflation cycle. Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan emphasized the need to see clear evidence of accelerating disinflation or further cooling in the labor market before supporting additional rate cuts.

UBS stated that this divergence means that if the Federal Reserve sticks to the original meeting schedule, the decision to cut rates will face significant controversy with only September employment data available. Some committee members may oppose immediate action on the grounds of insufficient data, while others may advocate for an early rate cut based on existing weak signals.

The report suggests that the Federal Reserve may believe that the risk of waiting until January to see weak labor market data is lower than the risk of cutting rates in December but subsequently seeing better data performance. This trade-off will determine the final timing choice.

If the decision is made to postpone the meeting, the market will receive clearer policy signals. If the original schedule is maintained, it indicates that the committee is willing to make judgments in the absence of complete data or has reached sufficient consensus on the December policy stance