Top 10 Influencers in 2025

Top 10 Influencers in 2025Glimmer Collection-43-《Song of the Great Wind》

Actually, I don't really know how to write articles; strictly speaking, deep down I'm just a country bumpkin. So don't expect me to support this or that. What I see and what I do—this is my world, and I only write about this. The world is created this way.

I've always believed that a person is a book. Between people and books, a torch in the courtyard burns through a thousand years of night.

I often wonder: In this life, are we reading books or writing them? From stone carvings to bamboo slips and silk scrolls, to the words on Xuan paper and A4 sheets, the sighs frozen in steles and wooden tablets—whose story is it, whose annals? A great wind rises and blows it all away. Now is the age of electronics.

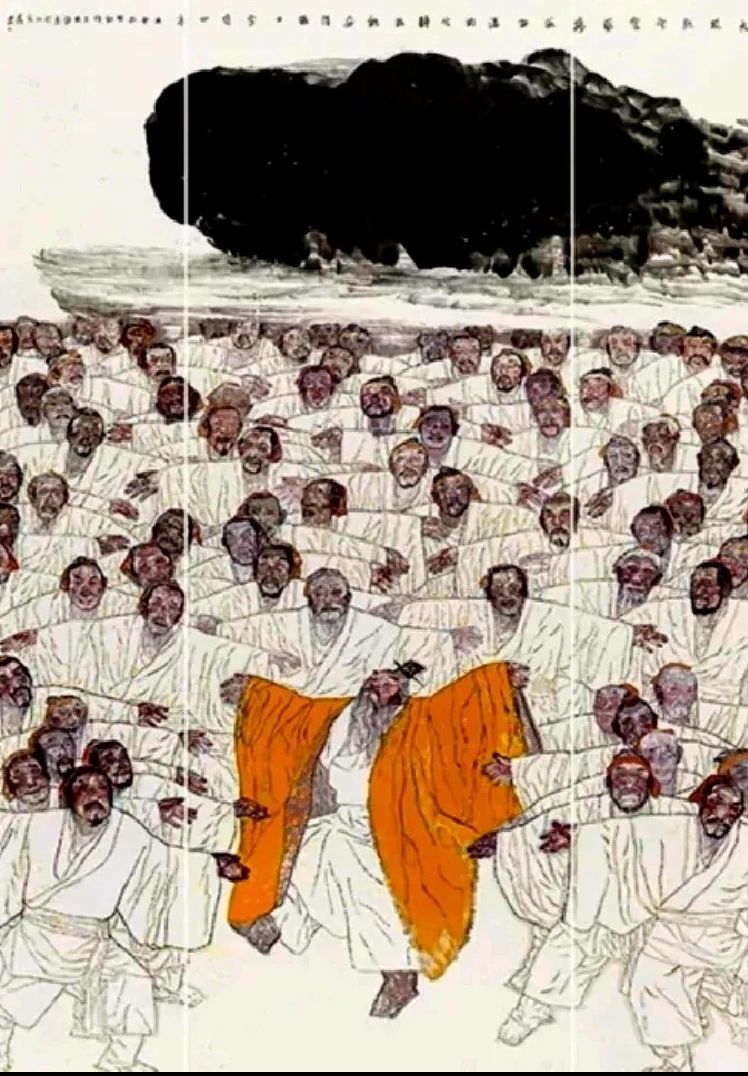

Emperor Gaozu danced with a torch in hand; a great wind swept in from the fields of Pei County, scattering the Qin tiles of Xianyang Palace and rippling the waters of the Wu River. He probably—no, he certainly—hadn't read ten thousand books. A chaotic era has no place for scholars; a fugitive from Dang Mountain, the snake-slayer of Mangdang, his teachers were the post roads of the Six States, the pass at Hangu, the wine cups at Hongmen. Every journey was a page soaked in blood and earth; every retreat was an annotation.

Heaven and earth are my teachers; the great path cloaks my body. This is the great wind as I understand it.

To fail is but to die; to succeed is to leave a name for eternity. Light, yet heavy as Mount Tai. It carries the full weight of an era.

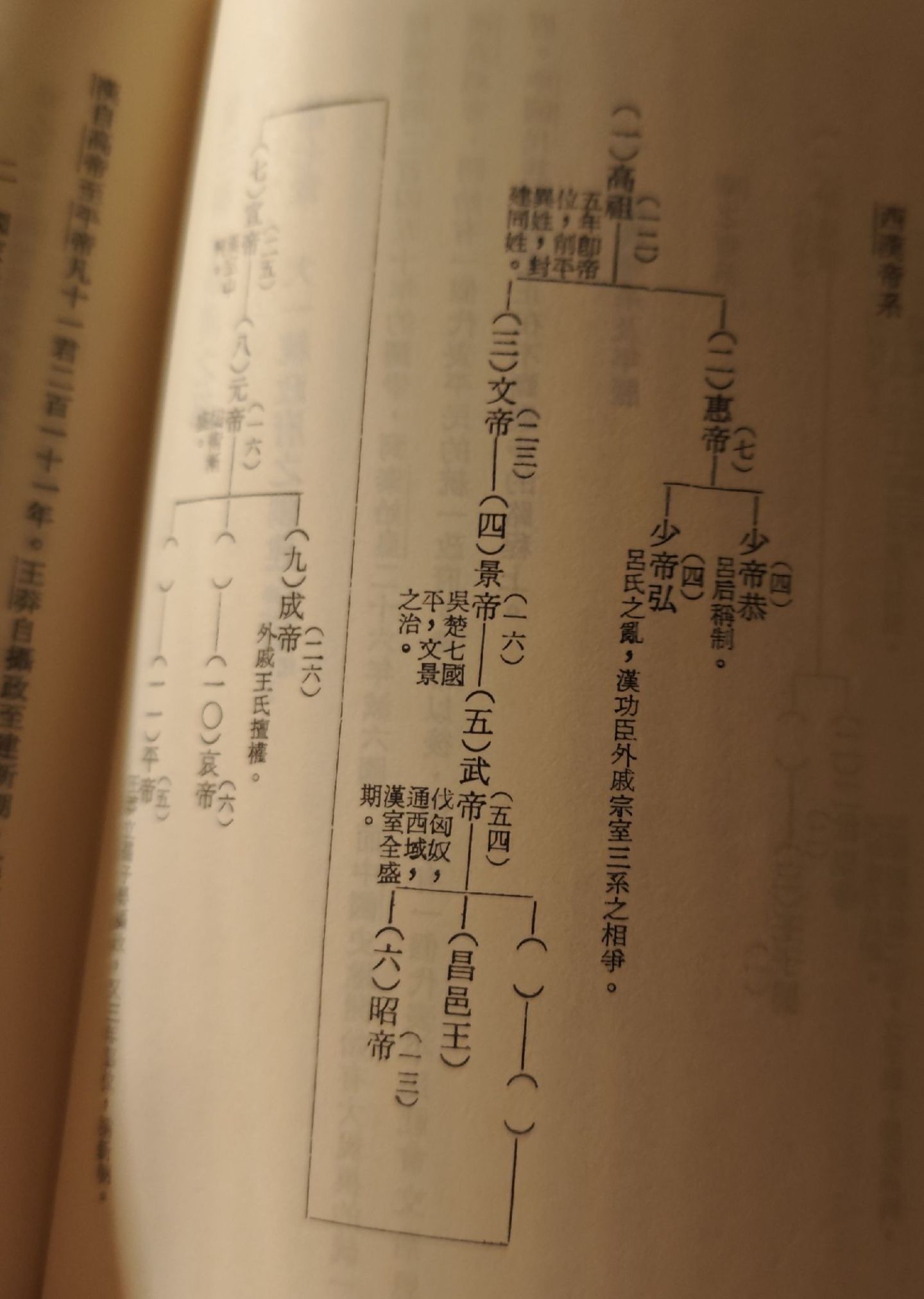

Open the *Records of the Grand Historian*, open the *Outline of National History*, and you can smell the mingled scent of dust and blood. From Chen Sheng's cry of "Are kings and nobles born to their stations?" to Xiang Yu burning the Epang Palace for three months of drifting smoke, to Han Xin's humiliation under the crotch. History has never been a docile transcription; it is an inscription carved on bone with the edge of a sword. So even if historians are castrated, they must write to the end, for this is a moral commitment, this is fate. Some things may be broken but not bent.

Liu Bang's path was from village head to emperor. What was on that path? The Feast at Hongmen, the seven days of snow when besieged at Baideng, the moment when Xiao He said, "Only magnificence can command awe" as the Weiyang Palace was completed. Every mile he walked later became a stroke on the map of the Han; every person he met later became a title in the annals.

The chariot of the Spring and Autumn period carried Confucius from Lu to Qi, from Wei to Chen, from Cai to Chu. Fourteen years of wandering, seventy-two disciples following, three thousand stories sprouting along the way. He did not write a book; he lived himself into a book. The *Analects* are fragments recorded by his disciples; the true *Spring and Autumn Annals* was the path he walked. On that path were sighs like "The Master said by the river," the hardship of running out of food in Chen and Cai, the sorrow of "My way is exhausted." So a person's life is but a silhouette pacing the stage.

What is a book? Words inked on bamboo slips? No, it is the trace of blood in the earth. A person is a book.

The night lit by the torch, the night when Gaozu danced under its light—all of Huaxia was watching.

The torch did not just illuminate an emperor or a dynasty, but the nascent outline of a nation. Before this, China was the rites and music of the Zhou kings, the laws of the Qin emperor; after this, China had another possibility. One that came from the wilds, from the earth, from the humblest yet capable of embracing the vastest heavens. Never broken, only because of the word "contain."

The *Song of the Great Wind*, just three lines, twenty-three characters:

"A great wind rises, clouds scatter and fly"—the weather of heaven and earth;

"My might covers the land, I return to my hometown"—the achievements of man;

"Where are the brave men to guard the four quarters?"—the eternal question.

Not "All under heaven is the king's land," but "Where are the brave men to guard the four quarters?" This anxiety made the Han an open vessel. Zhang Qian ventured beyond the Western Regions, Sima Qian's brush probed the barbarians, Huo Qubing's cavalry trampled the Qilian Mountains. This dynasty feared no mixing, no foreignness; it sought its form in fusion.

What struck me was how Napoleon praised Alexander the Great—that he worshipped Amun, and thus his conquest touched the soul, and so he conquered Egypt.

"Silver River" is the name of the Milky Way, and became the name of a people. What a wondrous coincidence, and yet how inevitable. A people who looked to the stars named themselves after a constellation. From then on, starlight flowed in our veins; in the West, it returns to one, for as Carl Sagan said, we are all made of starstuff.

Why this feeling for Liu Bang? Not because he was an ancestor.

Was Li Shimin not good? The Zhenguan golden age, the splendor of prosperity. But he was a noble of Guanlong, the young master of Taiyuan; his starting point was in the clouds. We look up to him as at a perfect statue. Too perfect, so perfect it's hard to approach. Was Zhu Yuanzhang not good? From beggar to emperor, a true rags-to-riches story. But his methods were too harsh—the Hu Weiyong case, the Lan Yu case, blood staining Jinling. His own fears ran too deep, so deep they had to be buried with countless heads. This is the act of a coward.

Only Liu Bang, a country bumpkin yet free-spirited; an emperor yet still carrying the air of the streets. He would curse, flee, return to Pei to drink and sing with the elders after achieving glory, hold Lady Qi and say, "Dance the Chu dance for me, and I will sing the Chu song for you." His humanity was not wholly warped by imperial power; his warmth was not wholly cooled by the throne.

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms was one of the most chaotic periods in Chinese history—fifty-three years, five dynasties, over a dozen regimes. Emperors changed like a revolving lantern; today donning the yellow robe, tomorrow headless. Yet in this chaos, a different vitality sprouted. The aristocratic families collapsed utterly; the great clans vanished like smoke. Anyone, if ruthless enough, strong enough, lucky enough, could become the Son of Heaven.

Zhao Kuangyin's coup at Chenqiao, Guo Wei and Chai Rong's repeat. Yet this emperor, a soldier by origin, dismissed his generals with a cup of wine, solving the chronic ailment of military interference in the gentlest way. Why? Because he understood those generals' minds—he had once been one of them. I won't judge his later years, but just for the phrase "From the masses, to the masses," he was truly a hero. A country bumpkin understands country bumpkins—this is empathy the nobility can never reach.

After all this, I'm not saying not to read books, but rather that books are not the path—though they can show you where the path lies. You can't just hold a map, see the signs, and think you know the world, that you need not walk.

Before Sima Qian wrote the *Records of the Grand Historian*, he traveled over half of China. He climbed Kuaiji, explored Yu's cave, peered into Jiuyi, floated the Yuan and Xiang, crossed the Wen and Si in the north, lectured in the capitals of Qi and Lu. Those ruins, those legends, those stories still passed down by word of mouth—they were the flesh and blood of his writing. Without these journeys, the *Records* would be just another dry chronicle. Why is it the "ultimate song of the historian"? Because:

To know this matter, you must walk it yourself.

So too Du Fu. Why are his poems called "poetic history"? Because he saw with his own eyes the "wine and meat stink behind vermilion gates, frozen bones litter the roads" of the Kaiyuan and Tianbao eras, lived through the "nation broken, mountains and rivers remain, spring in the city, grass and trees deep" of the An Lushan Rebellion, walked the "drifting, what am I like? A lone gull between heaven and earth" of exile, saw with his own eyes the night when officials seized men amid the people's misery. Every word is the echo of footsteps. Books are others' paths; paths are your own books.

Zhuge Liang knew the world would divide into three before leaving Longzhong because he had read enough books. In those books were Guan Zhong's strategies for ruling Qi, Yue Yi's plans for conquering Qi, Sun and Wu's tactics for war. But he truly became the Martial Marquis of Zhuge only after leaving his thatched hut—watching Zhou Yu set fire at Chibi, experiencing the dangers of Yizhou, the snows of Qishan, the winds of Wuzhangyuan. These are things no book could teach.

When the great wind rises, history is a long river; we are all its waters.

But! Some waters become waves, some foam, some sink to the riverbed, some rise as mist. Liu Bang was the one who stirred the great wave; his wave changed the river's course. Thus the old path: "A great wind rises, clouds scatter and fly."

Where does this wind come from? From Chen Sheng and Wu Guang's resolve to "die for the state," from Xiang Yu's arrogance of "I can replace him," from Han Xin's confidence of "the more, the better," from Xiao He's foresight in collecting the Qin's legal texts. This wind is the breath of countless people, the gathering of countless dreams; Liu Bang just happened to stand where the wind blew.

But that figure holding the torch and dancing has since been fixed in the nation's memory. Origins may be humble, knowledge shallow, but if you dare to walk and do not turn back, the path will stretch beneath your feet. To fail is but to return to dust; to succeed is to write history.

This is not just Liu Bang's story; it is the latent narrative of every Chinese. To talk all day of winning, only to lose everything in the end—that's no skill. A man may lose all his life, but the last time, he must win.

Finally, back to that character: Han. The Han of the Silver River.

A simple word, a complex people. Like the Milky Way, made of countless stars, each with its own light; together, a brilliant galaxy.

Han is the dynasty Liu Bang founded, but Han is also a shared name. It holds the romance of Chu lyrics, the rigor of Qin law, the breadth of Qi learning, the boldness of Zhao style. Zhang Qian brought back grapes and barbarian lutes, let Buddhism enter the Middle Kingdom, let barbarian dress and horseback archery blend into Hua-Xia robes.

The distinction between Hua and Yi? No, Han was never a closed castle but an open courtyard. It had thresholds, but the gates were always open. It had its core, but refused no fresh blood. The Qin lost its deer, and all under heaven chased it; whoever would make the Yellow and Yangtze flow backward is no longer Han, but a true rebel.

This is the true great wind—not a storm that destroys all, but one that lets clouds fly, eagles soar, seeds spread far. It has blown for two thousand years, to today's high winds, Gaozu's winds. Han is not and cannot be the cold wind from Prussia to Siberia.

Close the book in hand, look to the night sky outside the window. The galaxy is bright—which star is the torch Peigong held? Which wisp the wind Gaozu sang? It no longer matters.

What matters is that I am still walking, the path still stretches, the book is still being written.

Every living person is an unfinished book; every solid step is a line being written.

The world's wind is blowing, the era advancing; that day will not be slow in coming, that day is coming soon.

A great wind rises—

Walk, and sing.

The copyright of this article belongs to the original author/organization.

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not reflect the stance of the platform. The content is intended for investment reference purposes only and shall not be considered as investment advice. Please contact us if you have any questions or suggestions regarding the content services provided by the platform.