Is the See's Candies mentioned by Duan Yongping and Wang Shi really the "California Maotai"?

Hello everyone, I'm Jack.

I'm doing something foolish: writing about the long-lived companies in the S&P 500 in order of their founding dates.

Time is the most merciless judge in the business world, and also the fairest coronator.

From the canals and flour mills of the 18th century, to the railroads and steel of the 19th century, to the consumer goods and oil of the 20th century, and finally to the silicon chips of the 21st century. This is not just a list of the S&P 500, but a living history of the evolution of capitalism.

What we're looking for are the business secrets that have truly "anti-fragile" genes, having survived wars and depressions. Cutting through the fog of finance, we touch the pulse of industry, seeing how they've built moats against time over a century of storms.

This is a marathon about "value," and also an upgrade in cognition. I suggest following first, then reading. Picking up this scalpel to dissect business, we start with the oldest stories—let's begin now.

So far, I've reintroduced you to:

【1】Colgate-Palmolive, 1806

【2】Bunge Global, 1818

【3】McKesson, 1833

【4】Deere & Company, 1837

【5】P&G, 1837

-Main Text-

Recently, a video of Wang Shi in conversation with Duan Yongping went viral in my social circle.

"If we hadn't bought See's Candies, we might not have bought Coca-Cola.

See's Candies not only made us a lot of money, but more importantly, it eliminated our ignorance."

—Charlie Munger

Everyone was watching Duan Yongping's "relaxed vibe," seeing him chat about billion-dollar deals in sports shorts. But I noticed a very interesting detail.

When asked, "Do you still like Moutai now?" Duan Yongping didn't talk about the technology of sauce-flavor liquor or core assets, but casually said:

"See's Candies, (Moutai) is very much like See's Candies... it's very similar, so he (Buffett) bought the whole company (See's Candies). I don't have that much money, I can't buy the whole company (Moutai), but I can buy a little."

This sentence would make industry insiders' scalps tingle.

In Buffett's investment career, See's Candies is called "the dividing line between the Old and New Testaments of the Bible." Before buying it, Buffett was a disciple of Graham, liking to find bargains in the trash; after buying it, Buffett truly evolved and began heavily investing in those "crown jewels."

Today, let's take a closer look at this unassuming candy store. What magic does it have that made two top investment gurus from China and the US unanimously call it a "masterpiece"?

01

Not Just Candy, but "California's Hard Currency"

"If you can raise prices every year without losing market share, you have an excellent business."

—Warren Buffett

First, we need to understand what See's Candies actually sells.

On the surface, it sells chocolates and peanut brittle. But in reality, it sells "social security."

See's Candies was born in Los Angeles in 1921, founded by an old lady named Mary See. Over a hundred years later, its stores have hardly changed: black-and-white checkered floors, clerks in old-fashioned nurse uniforms, and that iconic photo of Mary See.

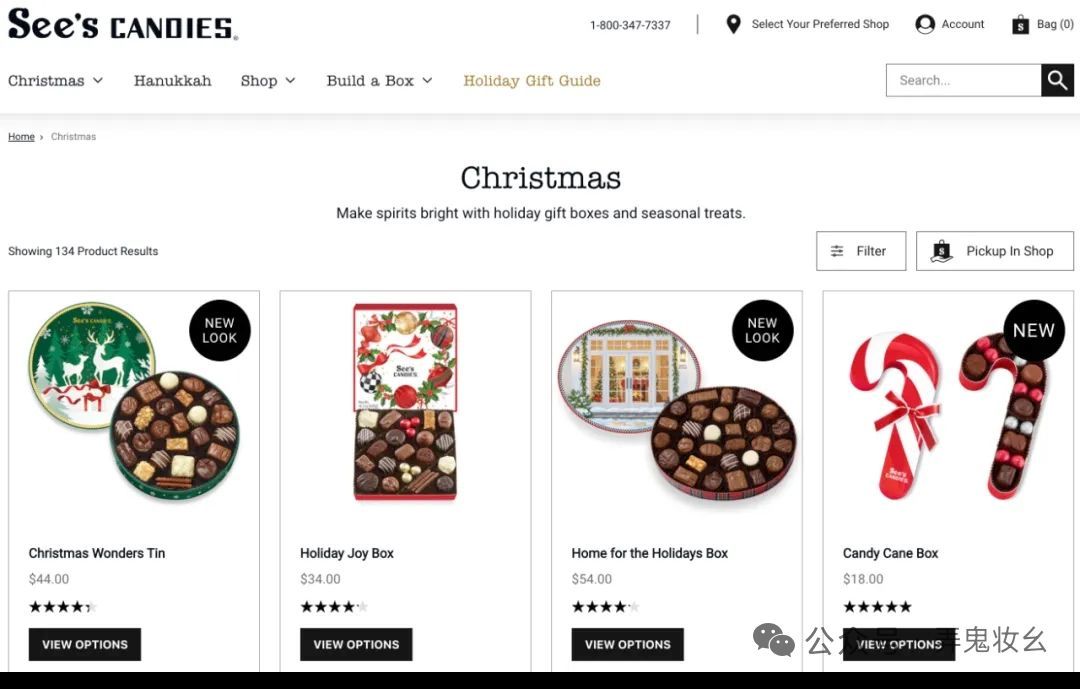

On the US West Coast, especially in California, See's Candies holds an extremely special position. It's not just a random snack on supermarket shelves; it's a "holiday necessity."

In Californian culture, bringing See's is the safest choice when a boy meets his future mother-in-law for the first time; giving See's as a Valentine's Day gift is the least likely to go wrong.

The best moat isn't cost advantage (because someone can always be cheaper than you), but irreplaceability. See's Candies is a classic case of "irreplaceability." In the minds of Californians, there's no "second-best" chocolate—only See's and everything else. This cognitive advantage is something competitors can't break no matter how much they spend.

This leads to an extremely powerful business attribute: pricing power.

If it's for yourself, you might switch brands over a dollar or two price increase. But what if it's a gift?

Would you dare to save a few bucks and buy a no-name chocolate for your girlfriend? You wouldn't. Because that would signal "lack of sincerity." In that specific context, price sensitivity is almost zero.

See's doesn't sell candy; it sells "persona masks"—symbolizing the giver's attention and sincerity. If you give your girlfriend a cheap box of chocolates, what you get isn't the joy of saving money but her disdain.

Thus, See's Candies enjoys a privilege that makes all businesspeople envious: an annual price increase on December 26th (after Christmas).

See's is the perfect case study for fighting inflation. When inflation hits and raw material costs (sugar, cocoa) rise, ordinary companies hesitate to raise prices for fear of losing customers, hurting their margins. But See's can raise prices beyond inflation (increase > inflation rate). This has allowed it not only to preserve value over decades but also to grow in real purchasing power.

The result? Consumers grumble but keep lining up to buy.

02

Not Tinkering Is the Highest-Level Strategy

"See that lady in the old-fashioned uniform, smiling as she hands you a free piece of chocolate.

That's not just marketing; it's part of the whole experience."

—Charlie Munger

Many companies die not because they don't try hard enough, but because they try too hard. Or, as we say now, "blindly compete."

The history of See's Candies is practically a textbook on "anti-competition."

Although See's has limited growth in scale (constrained by geography), it's a perfect Cash Cow. Its value lies not in becoming a Fortune 500 company itself, but in the cash flow it provides, which turned Berkshire into a Fortune 500 company. This is the value of a "niche."

In 1972, Buffett acquired See's for $25 million. The then-general manager Chuck Huggins asked Buffett, "Boss, what should we do next? Should we go global? Should we develop new flavors?"

Buffett only said one thing: "Don't change a thing."

This became the most important strategic turning point for See's in decades: stay the same.

First, resolutely stay out of supermarkets. This is See's most brilliant move. You see Hershey's, Mars, even Lindt, all scrambling to get into Walmart and Costco.

But See's refuses. It only sells in its own stores.

Why? Because once you're in a supermarket, you become just another SKU on the shelf, forced to compete on price, and your brand identity vanishes.

In your own store, you're the "experience," you're the "premium."

Second, build barriers with service. Anyone who's been to a See's store knows that whether you buy or not, the clerk will first hand you a free piece of chocolate.

That grandmotherly clerk in uniform, smiling as she gives you a guilt-inducing truffle. In that moment, driven by the human instinct of "reciprocity," it's hard to walk out empty-handed.

This is the origin of the "DTC (Direct-to-Consumer)" model. It bypasses middlemen, preserving extremely high margins.

Munger highly values See's old-school service style. He believes this unique experience builds an incredibly high competitive barrier. It's a kind of "association psychology": See's = happiness + nostalgia + premium service.

03

The Management Secret: Find a "Boring" Person

"See's Candies is the prototype of the business we dream about."

—Warren Buffett

What kind of CEO does a candy company need?

Not the kind who shouts "change the world" every day, nor the radical who wants to multiply sales tenfold. It needs a night watchman.

The current CEO, Pat Egan, is a fascinating case study.

What was he doing before taking over See's? He was a senior executive at Berkshire Hathaway Energy, managing Pacific Power and Nevada Energy.

From the power industry to selling candy—doesn't that sound absurd?

Actually, the logic is sound. What does the power industry value most? Stability, safety, reliability, no mess. That's exactly what See's needs.

The cultural core of See's is that photo of old lady Mary See, representing "Grandma's Promise"—Quality without Compromise.

After taking over, Pat Egan didn't make earth-shattering reforms but continued to uphold this "old-school" approach. His task is simple: ensure every piece of candy tastes the same as it did 100 years ago, and ensure every store maintains its service standards.

This "boring" management has achieved astonishing results:

Buffett marveled at See's minimal capital requirements. Even as sales multiplied, the working capital (inventory, receivables) and fixed assets (factories) needed barely increased.

When bought in 1972, sales were $30 million, profit $4 million; by 2007, sales were $380 million, profit $82 million. Over that period, only $40 million in capital was required. This means See's is a "perpetual motion machine"—the cash it generates doesn't need to feed itself; it can all go to feed Berkshire's other businesses.

Buffett invested $25 million to buy it. Over decades, See's hardly asked for another penny (because it didn't need new machines to expand) but instead handed over over $2 billion in pre-tax profits to Berkshire.

04

Why Understanding See's Means Understanding Moutai

Back to Duan Yongping's point. Why is Moutai still considered a good business even as retail prices fall and growth slows?

Because the essence of the business model hasn't changed.

Put See's and Moutai side by side, and you'll see they're practically twins:

Minimal reinvestment needs (ROIC approaches infinity): See's doesn't need to develop new flavors; Moutai doesn't need new recipes. Every penny they earn is free cash flow, not needing to go back into equipment. This is "making money while sleeping."

Inventory appreciation: Moutai even beats See's here. See's candy has a shelf life of months; Moutai gets more valuable with age.

Social currency attribute: See's is the face of Californians; Moutai is the face of Chinese. In an economic downturn, people might drink less, but as long as the "social game" exists, as long as the culture of relationships persists, Moutai's niche remains.

If you host an important dinner and don't serve Moutai, it's either because you think the occasion isn't that important or the guest isn't that important. The key is: what you think doesn't matter; what the guest thinks does.

Duan Yongping believes See's and Moutai are the same species. They both occupy a certain "cultural niche." See's and Moutai are essentially taxing human nature. As long as humans have vanity and social needs, these two businesses will always be money-printing machines.

05

Lessons for Investors

After See's story, what can ordinary investors learn?

Beware of companies that need to "keep running." Many companies seem to grow, but all the money they make must be reinvested in equipment, factories, R&D—stop, and they're obsolete. These are "money-eating machines." See's is a "money-spitting machine."

Seek "unchanging" value. Amazon's Bezos said: "People always ask me what will change in the next ten years, but the more important question is what won't change." People's craving for sugar won't change; their need for face won't change. Put your money in these unchanging lanes.

Very few businesses are worth "holding for ten years." Buffett calls See's "the prototype of a dream business." If you find a company that thrives just by raising prices with little effort, and competitors can't copy it no matter how they try, hold it, don't get off.

Finally

Great business models are rare. Companies like See's Candies are extremely special and scarce, true unicorns in the business jungle.

What's a unicorn? Those who haven't seen one don't believe it exists, no matter how you describe it.

With a good enough business model, mediocre management can sustain it (though good management makes it better). In contrast, tech companies (like Pinduoduo) need extremely smart management watching every day.

The world isn't fair, but investing is about finding opportunities in that unfairness.

If this article helped you understand a bit about business, hit "like," and we'll talk more next time.

End—Qin Wang circles the pillar.

This article was produced by an ordinary netizen using modern methods, with significant contributions from Gemini.

-END-

Hello everyone, I'm Jack.

I'm writing about the S&P 500 component companies in order of their founding dates.

Why am I doing this?

Because time is the most merciless judge in the business world, and also the fairest coronator.

In this series, I'll follow the guidance of the "Lindy Effect"—for things that don't die naturally (like technology, ideas, companies), the longer they've existed, the longer they're likely to exist in the future.

What we're dissecting isn't the rise and fall of a few K-lines, but the "bones" and "muscles" of business models. To this end, I've specifically excluded financials and utilities.

Why? Because banks and insurers' balance sheets are like opaque "black boxes," where leverage is both their oxygen and poison; while utilities are stable, they rely more on 特许经营权 and regulatory 红利, lacking the 野性 forged in free-market competition. We're looking for those "non-financial entities" that survived brutal free competition.

Writing about them one by one in order of founding, we'll see a grand panorama:

From the canals and flour mills of the 18th century, to the railroads and steel of the 19th, to the consumer goods and oil of the 20th, and finally the silicon chips of the 21st. This isn't just a list of the S&P 500, but a living history of capitalism's evolution.

In the journey ahead, I'll take you to uncover the secrets of "lasting enterprises," answering these core questions:

Cycle-proof genes: How have some companies survived the Civil War, the Great Depression, two World Wars, and the dot-com bubble, still standing tall? How did they manage "elephant pivots" amid technological upheavals?

The essence of moats: Is it unparalleled economies of scale? Brand mindsets that even resist inflation? Or some 极高 switching cost? We'll peel back 财报 numbers to see the underlying competitive edges.

First principles of business: Whether selling medicine, soda, or software, great businesses share underlying logic. We'll extract those "unchanging" truths from these centenarians.

Some call the S&P 500 "Blue Star Beta", meaning the average return of Earth's economic growth. But to me, these 500 companies hold the wisdom of human collaboration.

This is a long marathon. If you also believe in the power of "getting rich slowly," if you're also obsessively curious about "great businesses," follow me. We start with the oldest companies—this journey begins now.

Completed so far:

【4】Deere & Company, 1837: A 188-Year-Old Tractor Company Beat Tesla to Wheeled Robots?

【5】P&G, 1837: The 黄埔军校 of Global Business Leaders, Costco's Biggest Victim?

$PDD(PDD.US) $Berkshire Hathaway B(BRK.B.US) $Moutai(600519.SH)

The copyright of this article belongs to the original author/organization.

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not reflect the stance of the platform. The content is intended for investment reference purposes only and shall not be considered as investment advice. Please contact us if you have any questions or suggestions regarding the content services provided by the platform.